52 MONTHS > The birth of the Smithsonian’s 19th museum was recorded by EarthCam’s Gigapixel camera.

There it stands. No marble. No limestone. No white colonnades. Not a scintilla of the beaux-arts architecture that so thoroughly dominates the National Mall in Washington DC.

The Smithsonian’s new $540-million, National African American Museum of History and Culture (NAAMHC), which physically opened to great national fanfare last month, actually opened online in 2008 as a virtual museum, collecting stories, videos, photos, and other exhibits, curated online for a worldwide audience. But the goal, from Day 1, always had been also to create a physical, tangible manifestation of this unique story, and now that mission has been accomplished. And believe it or not, the fact that the new Smithsonian property has opened in the waning months of the last term of the first African-American U.S. President is truly a remarkable coincidence, not a planned legacy.

Indeed, the museum concept had been discussed in Washington decades before Barack Obama was even born. And today, just as he stands apart from his 43 predecessors in distinct ways, the new museum tells its story in forms, colors and massing that the Mall and the nation’s capital have never quite seen. And the story, itself, is unusual, because slavery and racism are inescapable, uncomfortable parts of its base narrative. “Americans aren’t used to being the ‘bad guys’,” explained Lonnie Bunch, former director of the Chicago History Museum and now founding director of NMAAHC.

Echoing that theme, President Obama said at the Sept. 24 opening ceremony, “(This) has been a long time coming, and will serve not just as a record of tragedy, but as a celebration of life.”

Proclaimed a joyful Bunch, “Today, a dream too long deferred is a dream no longer.”

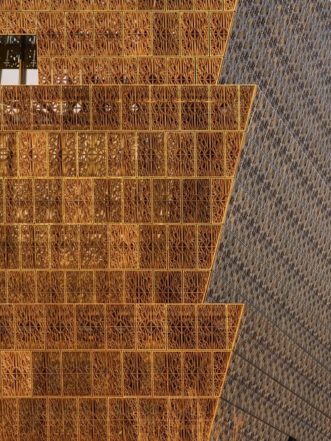

The three-tiered, 450,000-sq-ft facility, sited adjacent to the Washington Monument and home to 3,000 displays, resembles a Corona perched atop a Yoruban Caryatid, a traditional Nigerian wood column, according to David Adjaye, the mall’s lead architect and founder of Adjaye Associates. The sculpting is rendered by decorative lattice that, with the exception of a level glass base, encloses the five-story facility in 3,600 porous, bronze-colored, cast-aluminum panels, collectively weighing 230 tons.

“The pattern of the exterior panels evokes the look of ornate 19th-century latticework created by enslaved craftsmen in New Orleans that allows daylight to enter through dappled openings,” reads the description on the Smithsonian website. “At night, the Corona glows from within, presenting a stunning addition to the National Mall.”

“The density of the pattern is modulated to control the amount of sunlight and transparency,” Adjaye has said. “The corona is is based on elements of the Washington Monument, closely matching the 17-degree angle of the capstone. Panel size and pattern have been developed using the Monument stones as a reference.”

At a distance, few would guess a square-shaped, glass-enclosed structure lies beneath the upward-thrusting lattice, with panels and underlying glazing supported by a network of suspended interior trusses cantilevering off four concrete cores, and connected to networks of vertical trusses positioned between the two layers. From the outside, the museum simply resembles a nested, inverted pyramid.

Compelling story, cohesive team

It’s an audacious achievement for a city not always known for getting things done, and it came together at an historic site where conformity usually rules. Toss in the added challenges of federal bureaucracy and intense national scrutiny, and the fact that the Smithsonian’s diverse building team appears to have succeeded in honoring the project’s original vision is all the more remarkable.

Indeed, the 1860 Army of the Potomac may have numbered fewer than the mass of stakeholders involved in this high-profile project, famously sited on the National Mall’s last available plot of prime real estate. Backed by 32 consultants, the project team included a quartet of architects led by Adjaye, but including The Freelon Group (now part of Perkins + Will), Davis Brody Bond, and Smith Group/JJR. Their collective design was painstakingly brought to life by a trio of general contractors — Clark Construction Group, Smoot Construction, and H.J. Russell & Co. — plus dozens of subcontractors, and hundreds of skilled craftworkers and laborers. Also on board was engineering giant WSP/Parsons Brinckerhoff (WSP/PB), representing the owner to oversee M/E/P design, sustainable engineering initiatives, and construction equipment services, among other responsibilities.

Despite the number of players, “there was a real unity and cohesion on this project,” noted Clark SVP Brian Flegel. “Everyone was working together because this project is for every American citizen. That feeling permeated into interactions across the whole team. It helped keep [us] moving forward. If ever there was a challenge, we worked together to find a solution and make it work. The museum is meant to be a place for bridge-building and collaborating, and I feel our team embodied that from the start.”

“There was a real unity and cohesion on this project… The museum is meant to be a place for bridge-building and collaborating, and I feel our team embodied that from the start”

Not that stakeholders didn’t go their rounds — or face many hurdles — along the way. A very long way, as it happens.

In 1915, a group of aging African-American Civil War veterans first proposed that a national museum be devoted to the story of their struggle from slavery. Not surprisingly, the idea went nowhere, languishing through two World Wars, and even the Civil Rights movement. In the 1980s, however— not long after the network television miniseries Roots captured national attention — the concept of a museum dedicated to the circuitous journey of African-Americans brought here as slaves only to later become contributing citizens began to gather momentum. But cost considerations then stalled the idea again, until 2001. That year, at the behest of the Smithsonian, President George W. Bush signed legislation establishing a committee to evaluate the need for a museum. For years, both the commission and the Congress wrangled over a location before finally endorsing the prime plot on the Mall.

Following a design competition sponsored by NMAAHC, an architectural team was selected from a field of six. Along with other project team members, federal law mandated that the project undergo reviews and approval rights the National Capital Planning Commission (NCPC), the United States Commission of Fine Arts (CFA), and the D.C. Historic Preservation Commission (HPC).

“Working with the regulatory agencies was a challenge, and yet also quite productive,” recalled Philip Freelon, architect of record, and Freelon Group founder. “The CFA and NCPC were very interested in — some might say concerned about — the presence of a new building on the Mall.”

A primary bone of contention involved the latticework, originally designed as a bronze enclosure, not aluminum. Among other issues, “bronze proved heavy and therefore too costly,” recalled Hal Davis, a studio leader with SmithGroup JJR. But CFA was reluctant to abandon the bronze. “The commission members emphasized that treatment of the corona is the single most important element of the design,” noted CFA Secretary Thomas Luebke, writing in a 2012 letter to Smithsonian officials. Therefore, “they recommended that great attention be given to determine the final detail, finish, and color of the corona panels to achieve the intended lacy and glimmering effect.”

In other words, an agency with approval power over the project really cared about this issue, a lot.

“In the beginning, we were not 100% sure how were were going to do it, to be completely honest,” recalled Adjaye. After excavation commenced, a compromise involving aluminum panels with a five-coat “bronze finish” eventually was reached. Perfecting the color then required more than a year, as the design team tested and submitted candidates to CFA. The commission variously rejected several alternatives before choosing a polyvinyl difluoride coating system.

“It had that sparkle and luminosity we desired,” said Davis, who elaborated that each 3-x-5-ft panel was fabricated in three locations. Casting occurred at the first, machining at the second, and finishing at the third. Upon arrival on site, panels were then assembled, lifted, and hung on a steel subframe via cranes.

Other departures from original plans included losing the vertical wooden beams suspended from the first floor’s ceiling — “a shower of timber… to make you feel the weight of an enormous body of history,” said Adjaye early on, explaining his initial choice of the material. But Smithsonian officials later worried about potential warpage and the possible difficulty in upkeep. To Adjaye’s dismay, the costlier wood option lost out.

Making grades, Earning Gold

Due to D.C.’s well-known, historical height restrictions, the project team also needed to locate a full 60% of the museum in subterranean spaces. This became necessary after programmers and planners had decided to expand exhibit space with an organizational scheme that progressed from slavery and reconstruction, through to segregation and passage of the Civil Rights Act, all presented on four below-grade mezzanines. They complement the considerable education spaces, community gathering places and cultural galleries, all located above grade.

“The site was all swamp land,” noted architect Rob Anderson, a director with Davis Brody Bond. “When you dig down down 12 ft, you hit the water table… [so our] largest challenge was water.”

With that in mind, plans called for removal of 380,000 cu yds of dirt to dig 65 ft below grade, the deepest of any building on the Mall. But once work began, it soon became clear that the waterproofing plan would need revising after an excavation wall failed and ground water penetrated the perimeter. “Retaining walls were intended to waterproof below-grade foundation walls located 6 to 8 ft inboard, but obstructions in surrounding infill, including large boulders, created breaches that allowed water to penetrate them,” explained Davis.

Revisions called for waterproofing the foundation walls by creating a “bathtub enclosure structure.” Essentially, this formed a basement bucket, with walls rising 75 ft high to divert water and fully protect below-grade portions of the museum.

Above grade, the outer glass walls posed other challenges. Crews encountered tight tolerances for glazing due the size of individual members, ranging from 16-ft-high at grade level, to 23- to 25-ft-tall on upper levels. The pieces needed to be rendered by shop glazing 11-ft to 12-ft tall units into metal frames and combining pairs to create double-height members. Flatness was paramount, as was blast resistance — a modern security requirement for all buildings on the Mall — prompting the project team to source the glass from a German manufacturer, Davis said.

Of note, the new facility also is the first Smithsonian museum to achieve the USGBC’s LEED Gold certification. Designed to exceed ASHRAE 1-90 by more than 30%, sustainable components include: a 384-panel solar array; occupancy sensors and daylight harvesting; chilled beam units for office areas; demand-controlled ventilation; and a groundwater storage and reuse system. Meantime, the corona both provides shelter from the sun, even as it allows in ample natural light.

“These features are not only practical and sustainable from an architectural standpoint… but important in [achieving] LEED Gold certification,” said Paul Corrado, principal in charge for owner’s representat WSP/Parsons Brinckerhoff.

Architect of record Freelon also is pleased with the Corona, albeit for different reasons. The building is “distinctive and rightfully so,” he told reporters. “I don’t think it is disrespectful or overly aggressive in how it diverges from the norm. Because the materiality and color are so dynamic it could almost be ablaze at times, and at other times it is brownish and quiet. I love that about the facade. White marble is going to look pretty much the same every day.”

So, just as so many African-American gifts and traditions have upended convention and broadened the melting pot of our national culture, so too now has this new museum enriched the National Mall.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________

Rob McManamy contributed to this story.

Discussion

Be the first to leave a comment.

You must be a member of the BuiltWorlds community to join the discussion.