Fantasy Football? Stadium Deals Abound Despite Track Record

by JOHN GREGERSON | Feb 29, 2016

“Build it and they will come.”

Well, not always. (And if they do, they may not stay.)

That familiar line from the film Field of Dreams certainly made for a memorable Hollywood theme. But on this chilly morning after the Oscars, reality is usually there to rudely rouse us from our slumber. Then again, the sports construction market seems perpetually to exist in an amnesiac fantasy that even Tinseltown must envy. Financial flop after flop, the inelastic, irrational market continues to attract billions in public-private investments.

Just across town from the Academy Awards, in fact, construction is now under way on a $2.6-billion, 300-acre, HKS-designed NFL Entertainment District for the Rams football team, which is returning to Los Angeles next fall after 20 years in St. Louis.

But the competitive dynamic between St. Louis and Los Angeles is just one of the many subplots that have already typified the post-Super Bowl start of this off-season. At present, several new state-of-the-art stadiums are under negotiation, with team owners claiming they need new facilities to boost attendance, consolidate fan bases and compete to host to future Super Bowls. But the maneuvers will likely bruise taxpayers, who often contribute mightily to new stadium costs and foot the bill for related infrastructure upgrades. And when franchises choose to relocate, the public is the one left holding the bag, forced to maintain empty, existing facilities until new tenants can be recruited.

Hitting home, Keeping Up

In such instances, local design and construction communities also take a licking, losing out on highly lucrative contracts and thousands of jobs. Case in point: When the St. Louis Rams announced in January that they had decided to head back to sunny L.A., the news not only was met with hard feelings among fans, but left taxpayers on the hook for $16 million that the city had already allocated toward plans for a new $1.1-billion stadium it hoped would convince the Rams to stay put.

It didn’t and they aren’t, though St. Louis-based stadium designer HOK reportedly collected $10.5 million for its work on the project. Rams owner Stan Kroenke found the planned stadium inadequate, bluntly adding that it would amount to “financial ruin” to any NFL team that bought into it.

Among other issues, the decision to relocate the Rams is rooted in a longstanding dispute between city and franchise over funding for renovations to Edward Jones Dome, home to the Rams since 1995. At that time, a “first tier” contractual clause stipulated that the State of Missouri, the city and county all would ensure that the newly constructed facility would retain its status as one of the NFL’s top eight venues. As years passed, however, the Jones Dome lost ground to new, billion-dollar state-of-the art stadiums in New Jersey, Texas and California. When upgrades failed to materialize in St. Louis, Kroenke sought $700 million for improvements in 2013. City officials declined.

Kroenke subsequently purchased land in Inglewood CA, near LAX Airport, signaling that he had had it with St. Louis. “We have to have a first-class stadium product,” he said at the January press conference.

Ironically, Kroenke and a private partner will bankroll a substantial sum for the new Inglewood Stadium, scheduled to open in fall 2019, but the team’s defection has brought the long-simmering debate over public funding for entertainment facilities to a boil, especially in Souther California. There, the San Diego Chargers are currently shopping for a new home, as well. Should the team fail to secure funding and site selection for a new stadium of its own, it has recently brokered a deal with the NFL that would give it the option of sharing the Rams’ new temporary home at the 93-year-old Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum beginning in 2017. If the Chargers pass on the option, the league would then extend the offer to the well-traveled Oakland Raiders. Coincidentally, the Coliseum, which also is the home field for the University of Southern California, announced its own $270-million renovation in October.

RELOCATION Brinksmanship

Both the Chargers and Raiders have faced uphill battles to construct new facilities, and their threats of relocation are an old NFL ploy often used by teams to pressure host cities. Once their local fan base is engaged, it usually is enough to bring parties to the table to hammer out funding, site selection, lease details and other issues. So, not surprisingly, Raiders owner Mark Davis has said openly that he is shopping the franchise to San Antonio and Las Vegas, even as Oakland Mayor Libby Schaaf says she is eager to negotiate a new deal. If Schaaf fails to prevail – she has indicated she anticipates minimal public investment for the project – then Oakland could find itself without a team yet again. The same holds true in San Diego, where the city is still trying to persuade the Chargers to stay.

“(Public subsidies) amount to money being taken from struggling tax payers by politicians, then funneled to billionaire owners of teams in order to reduce overhead and increase profits”

Should negotiations with either franchise come to include significant public investment, expect some push back. According to the Washington DC-based watchdog, Taxpayers Protection Alliance (TPA), pubic subsidies for stadium construction and renovation projects “amount to money being taken from struggling tax payers by politicians, then funneled to billionaire owners of the teams in order to reduce their overhead cost and increase their profits.”

$7 BILLION AND COUNTING

Since 1995, 29 of 31 NFL stadium projects have received taxpayer funding, typically in the range of 50% to 75% of construction costs, and collectively totaling $7 billion, according to TPA. For the $720-million Indianapolis Colts‘ Lucas Oil Stadium, completed in 2008, public financing amounted to 86% of the final tab. The two privately funded exceptions are 2010’s MetLife Stadium, built for NYC’s Giants and Jets franchises in East Rutherford, NJ, and the Miami Dolphins Sun Life Stadium, constructed in 1987 and located in Miami Gardens FL.

New Vikings Stadium‘s $1.1-bil tab is being split with taxpayers.

Among current projects, taxpayers are contributing $506 million for a new $1.1-billion Minnesota Vikings stadium due for completion this year.

Both government officials and franchises contend that taxpayers invariably benefit from their contributions, since the stadiums presumably create jobs and boost local economies. “[But] most jobs are temporary and involve stadium construction,” says TPA President David Williams. Promises of new development, including restaurants, retail and hotels, sprouting up around the new facilities often fail to materialize, and tourist dollars dedicated to ticket sales often come at the expense of other local tourist destinations, making for a net-zero gain, Williams contends.

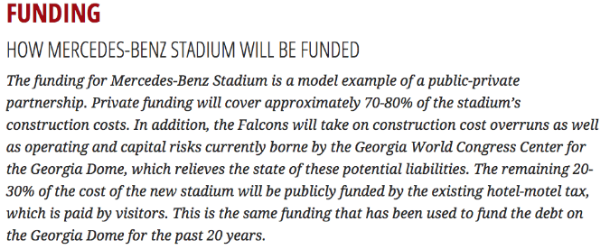

Meanwhile, the Atlanta Falcons‘ new $1.4-billion Mercedes-Benz Stadium is aiming to be ready for the 2017 season. Using a public-private partnership (P3) approach, the team claims that more than $1 billion of its total costs will not be borne by the public.

FINANCING Ingenuity

Unlike infrastructure projects involving roads, bridges, and utilities, the public benefit of funding privately-owned professional sports projects is not at all clear. So, realizing that their plea for public dollars is no longer an easy sale — especially at a time when so many states, cities, and municipalities are operating in the red — team owners have become increasingly open to pursuing creative funding alternatives that are advantageous to both their franchises and taxpayers.

In 2014, for instance, Miami Dolphins owner Steve Ross struck a deal with Miami-Dade County that would provide bonus payments to the franchise for hosting marquee events in exchange for the team assuming financial responsibility for a $350-million stadium upgrade.

Under the agreement, the franchise will earn a Performance-based Marquee Event Grant after the stadium hosts specified events, including a Super Bowl and a World Cup final ($4 million), a college football championship, a World Cup soccer match ($3 million), a college football semifinal ($2 million) and an international soccer match ($750,000). Grant payments would derive from the county’s portion of available Convention Development Tax funds.

Miami mix: The Dolphins are spending $350 million on upgrades, but will earn grants by hosting non-NFL events.

Meantime, it’s business as usual in San Diego, where stakeholders broke off negotiations for a new stadium after an August 2015 proposal prepared by the city and San Diego County failed to satisfy the Chargers franchise, says Matt Awbrey, spokesman with San Diego Mayor Kevin L. Faulcone. As outlined in the plan, the Chargers would have contributed $363 million to the new $1.1-billion stadium, the public $350 million, with the NFL kicking in $200 million and personal seat licenses (PSLs) accounting for $187 million of funding. A major sticking point: the Chargers weren’t enthusiastic about remaining in its current location, Mission Valley, as compared to moving to the city’s downtown waterfront, where the team envisions a $1.4-billion multi-use development that would accommodate a stadium, an exhibition hall below it, and meeting room and ballroom space in an adjoining building, all with views of the field, San Diego Bay and the Pacific Ocean.

Among other benefits, the Chargers contend the plan would be attractive to taxpayers, since the complex would accommodate concerts and other public events. The plan also would shave $400 million off construction costs if the stadium and exhibit hall were built separately, the team claims. Although P3s didn’t figure into their August proposal, Awbrey says the city and county wouldn’t rule out the concept if and when the Chargers return to the table.

“There are a lot of options we’d be looking at,” Awbrey says, “and the Mayor is open to listening to and discussing any viable plan the Chargers may put forth.”

Earlier this month, Chargers chairman Dean Spanos hired businessman and former developer Fred Maas to lead a citizens’ initiative to get a measure for a new stadium on a November ballot. Among other provisions, the initiative would hike hotel occupancy taxes from 10.5% to 15.5% to help pay for the new facility.

Similarly, the original August proposal proffered by the city and county also would have put $350 million in public funding to a public vote on local ballots.

So, depending on how matters resolve, taxpayers may finally have their say on this matter, at least in San Diego. However, the ever-popular NFL may well discover then that non-football fans also vote.

No worries, though.

There always seems to be another U.S. city, solvent or not, that is anxious to step in.

BuiltWorlds’ Rob McManamy also contributed to this report.

Discussion

Be the first to leave a comment.

You must be a member of the BuiltWorlds community to join the discussion.