Table of Contents

II. Introduction & Overview Of Chicago’s Entrepreneurial Ecosystem

III. Chicago’s Built World Tech Companies

A. Grouped By Company Size / Number Of Employees

B. Grouped By “Specialty” / Technology / Function

2. Least Popular “Specialties”

C. Grouped By “Sector” / Market / Vertical

3. Environmental, Social & Governance (“ESG”), Water, & Energy

4. Technical Services Providers

5. Manufacturing, Processing, and Equipment

6. General Business Solutions & Other Miscellaneous

IV. Looking Ahead / Where We Go From Here

A. How Might We Measure An Entrepreneurial Ecosystem?

I. Executive Summary

BuiltWorlds commissioned this research report for Chicago‐based members who are interested in growing the local built world tech ecosystem. The BuiltWorlds research team compiled most of the company data and provided it to Entropy for review, analysis, research, and report development. The primary goal of this report was to establish a reasonable baseline upon which to measure future growth of the Chicago built world tech ecosystem.1

The report is structured as follows. Section II will provide an introduction and overview of Chicago’s entrepreneurial ecosystem, how it came to be, and some important takeaways. Section III will dive into the dataset of over 200 technology companies in the Chicagoland area operating either in the built world, or in adjacent industries—some are “startups” today, some were “startups” long ago, and others are “non‐startups” that service our industry in other unique ways. Section IV will prompt some discussion by asking some key questions regarding potential next steps.

Regarding the data analysis section of this report (i.e., Section III), the findings were as follows:

- Of the 212 tech companies in the dataset, 52 employ between 1 and 10 people, 73

employ 11 to 50 people, 56 employ 51 to 250 people, and 31 employ 250+ people. - The Top 5 “Specialties” among Chicago built world tech companies were Data Analytics,

Collaboration & Documentation, Real Estate, AI/Machine Learning, and Project Mgmt. - “Specialties” such as QA/QC, Scheduling, Insurance, Labor Marketplaces, Permitting,

Supply Chain, and Urban Planning represent potential gaps or opportunities locally. - In general, Chicago’s built world tech companies are: (1) highly diversified (i.e., there is

no dominant theme), and (2) strong in B2B—consistent with the Citywide economy. - Additional topics for future consideration include: (a) measuring progress, (b) identifying

key roles (e.g., venture capital, AECO players), (c) collaboration opportunities (e.g., P33

Chicago), and (d) having fun growing the local built world tech ecosystem.

II. Introduction & Overview Of Chicago’s Entrepreneurial Ecosystem

“Chicago hasn’t been traditionally known for innovation.”2 This was the opening sentence of a blog post written by someone who is not from Chicago...probably from one of those “coasts.” I’m not saying he’s wrong, by the way. It’s his opinion, clearly. But the sentence (...conclusory, as written) gave me some pause—and prompted me to do a little research. Here’s a list of select Chicago innovations of the past 100 years. And no, we lifelong Chicagoans do NOT have a chip on our shoulder:

- The Nuclear Reaction

- The Cellular Phone

- The First Skyscraper

- Mail‐Order Retail

- The Ferris Wheel

- Reversing The Chicago River

- The Zipper

- The Softball Game

- Deep‐Dish Pizza

- Michael Jordan3

Oh, and let’s not forget the 1893 World’s Fair, which took place just 22 years after the Great Chicago Fire of 1871—an amazing engineering and construction feat in any era...let alone 130 years ago. And, despite its darker side, the story of the 1893 World’s Fair (also known as the “White City”) is a rather important one in Chicago’s past. In fact, the White City, together with the urban planning efforts of Daniel Burnham and others, are among the most important pieces of Chicago’s built world history.

Now, in fairness to the blogger, that 2015 post went on to praise Chicago for its relatively new (...at the time) tech incubator, 1871, calling it a “model for innovation.” Given the growth of Chicago tech and innovation over the years, I think most people can get on board with that opinion. Thanks to the efforts of local innovators, entrepreneurs, and community leaders (...too many to name here), a strong foundation was laid—ready to build upon.

Note to the reader: The primary source for the rest of this opening section is a Harvard Business School [HBS] case study titled, “Rising From the Ashes: The Emergence of Chicago’s Entrepreneurial Ecosystem”, by Lynda Applegate, Alexander Meyer, and Talia Varley. This summary level citation is provided in lieu of adding footnotes throughout the remainder of this section.

Before diving into Chicago‐based, built world tech companies, it’s important to lay the groundwork for Chicago’s entrepreneurial ecosystem. One of the most important points about Chicago that many people often overlook or take for granted is the fact that Chicago has one of the most diversified economies in the world. This was well understood by Chicago’s business leaders of the past, and something that modern day business leaders sought to take advantage of too:

While many ... attempted to copy successful entrepreneurial ecosystems in Silicon Valley, Boston or New York, the business leaders that laid the foundation for Chicago’s ... ecosystem between 2000 and 2015 avoided this common mistake and built on Chicago’s strengths. Specifically, Chicago was recognized as having one of the world’s largest and most diversified economies, with more than four million employees that, in 2015, generated an annual gross regional product (GRP) of over $575 billion. [Emphasis added]

That said, diversification in business can cut both ways. On the positive side, diversification makes an economy robust and anti‐fragile to “Black Swan‐type” events.4 In fact, Chicago’s diversified economy did allow it to rebound quicker than many places in the country following the Great Recession of 2008. But the downside of Chicago’s highly diversified economy is that it can feel large and unwieldly, and therefore lacking a “dominant theme” or obvious specialization. As the HBS case states:

Some ... questioned whether the city’s industrial diversity was a double‐edged sword. While a powerful source of stability and diversification for the city and a major benefit to ... startups, was this diversity also leading to a[n] ... ecosystem without a dominant theme?

Interestingly, the AEC industry seems to grapple with a similar double‐edged sword in the form of diversified project teams, subject matter expertise, and competing interests in the way contracts are

set up. On the one hand, diversified project teams with a variety of disciplines are capable of generating incredible outcomes in the form of engineering and construction feats; on the other hand, they can also

breed conflict. For instance, the AECO industry’s collective diversification can also lead to contract disputes, including for example who is responsible for delays and overruns when something goes wrong.

This leads to the outside perception of a contentious, highly fragmented industry. Again, diversification cuts both ways—it depends on how you look at it.

In an effort to capitalize on its diversified economy, Chicago’s business leaders also consciously sought to “build bridges” between early‐stage companies and the large corporations based in and around the Chicagoland area including the decision where to locate 1871:

Commenting on the strategic decision behind 1871’s location after reviewing 200

potential sites, Collens [of Pritzker Group Venture Capital firm] explained, “We wanted to be in the center of the business district and to make sure that there was an opportunity to build bridges between startups and the established business community.” [Emphasis added]

This strategic decision was in sharp contrast with Silicon Valley’s “pattern of building consumer‐focused apps.” The strength of Chicago’s B2B edge is a recurring theme from local business leaders, including

current Illinois Governor and longtime investor J.B. Pritzker, who encouraged “[Executives in large, established companies] ... [to] think of startups as R&D. They’re very inexpensive R&D and [they are]

free from the shackles of corporate bureaucracy.”

Another local entrepreneur, Pete Georgiadis of Synetro Group, emphasized some of the benefits of the B2B strength for Chicago‐based entrepreneurs especially in the early stages:

If you’re based in Chicago, you don’t have to go anywhere else to test a new business concept. You can do your minimum viable product and you can get your data here no matter what kind of product you have. And when it comes to B2B, there is a large and diverse set of big companies here who can be customers, partners, sources of talent and even acquirers.

This trend of capitalizing on B2B needs is also evidenced by the founding of TechNexus, the “venture collaborative” established in 2007, which seeks to match‐make large corporate clients with startups in

its portfolio and extended network.

Interestingly, among the first B2B, built world tech companies in Chicago to really take off was GradeBeam, a coop formed by Walsh, Graycor, Pepper, Bulley & Andrews, and W.E. O’Neil in 2001. The story of GradeBeam, which sought to streamline the bidding process for projects, is worthy of its own piece—so we won’t attempt to tell the full story here. However, importantly, GradeBeam, acquired by Textura in 2011 (then Oracle in 2016), was among the first built world tech companies—and it started right here in Chicago over 20 years ago.

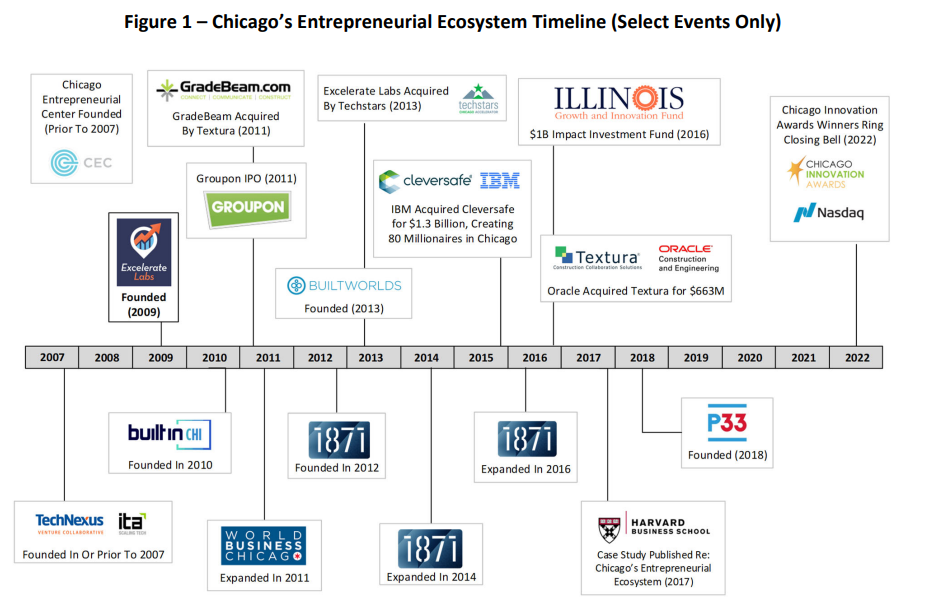

Figure 1 below shows a timeline of select events in Chicago’s entrepreneurial ecosystem history between 2007 and today:

While nowhere near comprehensive, the above history provides a glimpse into how the Chicago

entrepreneurial ecosystem came to be. In the next section, we’ll talk about the subset of built world

tech companies within this broader ecosystem.

III. Chicago’s Built World Tech Companies

The primary data source for this section of the report is the BuiltWorlds Company Database. The database goes beyond just the member companies. In other words, it’s the accumulation of various past efforts by the BuiltWorlds Research Team, and from time to time gets updated as the landscape

continues to evolve including new entrants or acquisitions. The data generally includes the following fields:

- Company Name,

- Company Type (in this case, all were tagged as “Technology” companies),

- Company Specialty (companies could choose more than one Specialty),

- City, State/Region, and

- Number Of Employees

We also added a new field for the purposes of this baseline report, called “Sector” to map the relatively broad, diversified dataset among different markets or verticals. “Sectors” identified amongst the 200+

companies were:

- Con‐Tech,

- Prop‐Tech,

- ESG/Water/Energy,

- Technical Services Providers,

- Manufacturing, Processing, and Equipment,

- General Business Solutions and Other Miscellaneous.

To start, the research team cast a relatively wide net by filtering for all Illinois‐based, “Technology” companies in the database (i.e., not just “Chicago”). This was to ensure companies based in the greater Chicago area were captured as well, and not just those based in downtown Chicago. Steps such as these were taken by the team as part of an iterative approach to identifying potential “built world” tech companies in Chicagoland for further analysis. We expect to further refine the list

moving forward.5

The current dataset includes 212 “Technology” companies. Some companies self‐identified as

“Technology” if, for example, they added themselves to the BuiltWorlds database. Others were tagged

by the BuiltWorlds Research Team as “Technology” companies—these generally included non‐member

companies. In general, most companies that added themselves to the database also identified at least

one “Specialty” as part of that process—while others do not have a Specialty identified.

Upon initial review of the data, we noted certain one‐off issues (e.g., a company might’ve listed

itself as based in “Chicago” but may be principally located elsewhere). Examples include international

startups with a US office in Chicago, or startups originally founded in Chicago that are now 100%

remote. Due to the uniqueness of these one‐off issues, we elected not to remove any companies from

the dataset; rather, we left them in the study with this as the appropriate qualifier. Other examples of

companies not removed included: (1) those operating in industries adjacent to con‐tech or prop‐tech

(e.g., manufacturing), (2) firms whose core business includes physical products (e.g., Grainger) or

technical services (e.g., digital transformation consulting or app development), and (3) companies that

may no longer be operating under the identified name (e.g., the company may have merged or been

acquired, or its website is simply no longer active).6

Why leave these companies in? Well, because they’re part of the overall story of Chicago’s

diverse built world ecosystem. To pull them out altogether wouldn’t give us the opportunity to talk

about them and learn from them—which ultimately is how we intend to use this report. Put another

way, not only do we want to look at data within our narrow space (i.e., just con‐tech, or just prop‐tech).

We also want to look at fringe data to understand where the lines are. We also don’t want to miss

opportunities to cross‐pollinate with companies not currently focused in construction. More on that

later, but the point is there are lots of reasons not to exclude these types of companies at this point.

It’s also important to remind ourselves that we’re not just trying to get the most precise count

(...although at some point we hope to get close to that number). Our goal is to grow the ecosystem,

plain and simple. And, as we will see later, there are lots of ways to go about that, and lots of different

ways to measure it too.

The following sections present company data grouped by Size, Specialty, and Sector, together

with various observations or questions for the group to think about moving forward.

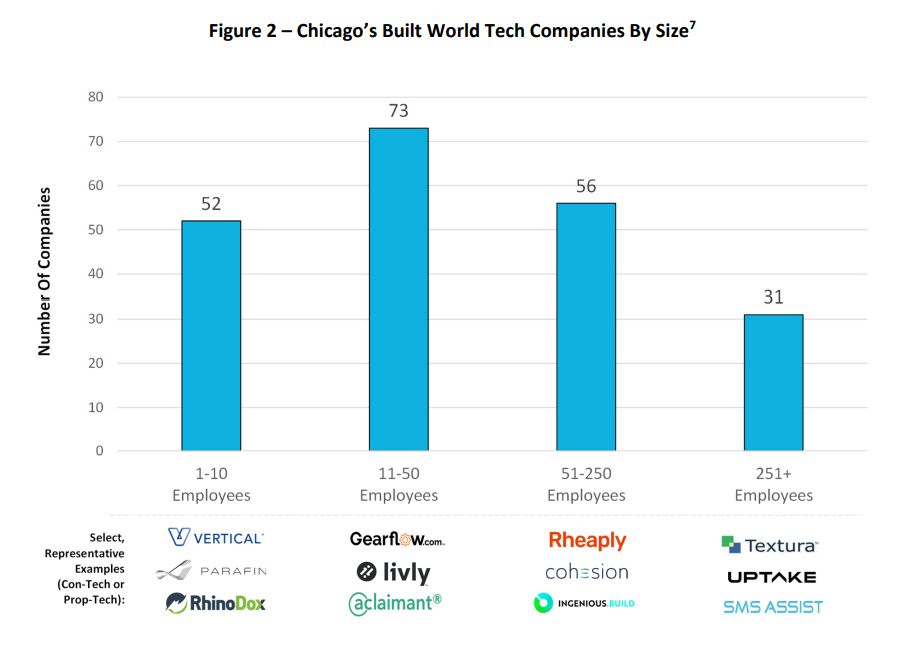

A. Grouped By Company Size / Number Of Employees

Figure 2 below provides a high‐level overview of the available dataset based on company size, as

defined by number of employees. Of the 212 tech companies in the dataset, 52 employ between 1 and

10 people, 73 employ between 11 and 50 people, 56 employ between 51 and 250 people, and 31

employ more than 250 people. Also shown below each of the data points are select, representative

examples of startups in the con‐tech or prop‐tech spaces specifically.

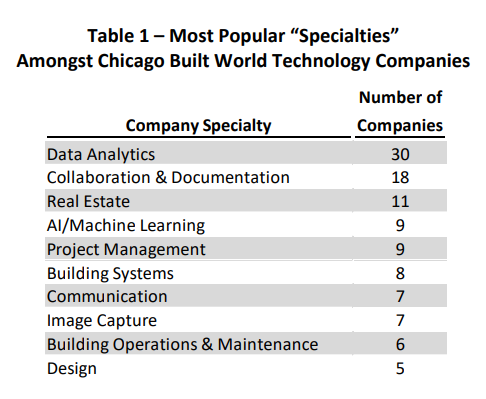

B. Grouped By “Specialty” / Technology / Function

Upon joining the network, BuiltWorlds member companies each select “Specialties” from a pre‐

populated list, as well as non‐member companies that add themselves to the database. A “Specialty”

could be a technology (e.g., AI/Machine Learning), or a function (e.g., Project Management), or both.

Companies can select more than one “Specialty.”

Of the 212 companies, approximately two‐thirds (or 133 companies) identified one or more

Specialties.8 In total, the 133 companies selected 225 Specialties—again, since companies could select

more than one Specialty. While only 63% of the total (133/212), this sample is still helpful to try and

understand which Specialties or technologies in the market might be overly crowded, versus potential

“white space” opportunities. The next two sections address these extremes by highlighting some of the

most and least popular Specialties.9

1. Most Popular “Specialties”

The top 10 Specialties identified by Chicago built world technology companies are shown in

Table 1, along with the number of instances of each. Data Analytics was the most popular Specialty,

with just under 25% of companies (30 of 133) identifying it as one of its specialties. Second on the list

was Collaboration & Documentation with 18 companies, third was Real Estate with 11 companies—and

so on down the list.

The above list should be generally consistent with what most people in con‐tech or prop‐tech would expect. In fact, this reasonableness check helps to validate the dataset of a diversified economy. In other words, from this data one could argue that Chicago’s diversified economy generally represents the broader built environment, and therefore may deliver the benefits of a “microcosm.” We saw this same idea referenced earlier in the HBS case when a local entrepreneur emphasized that, “[i]f you’re based in Chicago, you don’t have to go anywhere else to test a new business concept. ... there is a ... diverse set of big companies here who can be customers, partners, sources of talent and even acquirers.”

Startups might also benefit from the above list in terms of their marketing. For example,

startups pitching “Data Analytics” as a value proposition may struggle to differentiate themselves since

it’s now such a popular term in both con‐tech and prop‐tech. It’s meaning has been somewhat diluted.

Interestingly, we’re starting to see this in the reality capture market as it continues to get more and more crowded. Some companies are trying, it seems, to recategorize their offering with a new phrase or tag line to differentiate themselves. Some have done so effectively, while others continue to struggle

to articulate a competitive advantage.

On the non‐startup side, many technical service providers also seem to advertise Data Analytics as one of their offerings—another likely reason for the high count of that Specialty. Cloud‐based systems have also generated a shift in the way we store and host data, enabling technical services firms to market “Collaboration & Documentation” solutions—the second most popular on the list. As we all know by now, the industry was headed towards more web‐based apps and cloud‐based systems. COVID only accelerated that. As a result though, startups in the built space might be wise to skip the cost‐benefit of not needing a physical presence onsite—since that benefit is arguably “table stakes” by now (i.e., the new standard is remote access). Therefore, in lieu of trying to cost justify the solution with the avoidance of travel costs, startups might consider spending more time on product demos and feedback, with the goal of selling a best‐in‐class solution among the many competitors. In fact, it might even make sense to identify those competitors by name to help orient potential customers.

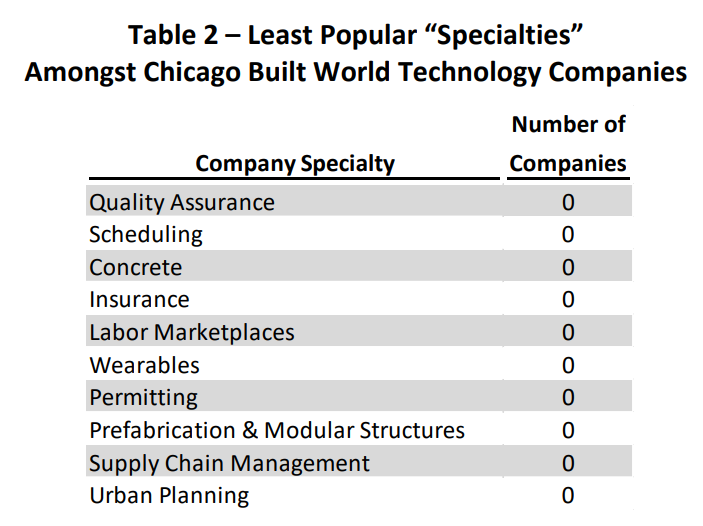

2. Least Popular “Specialties”

Several Specialty areas do not appear to be addressed by any Chicago‐based company, at least

based on the current dataset. Below are 10 select, representative examples of Specialties in which no

Chicago built world technology companies self‐identified (Note: There are others):

Some of these are well‐addressed in the broader built world market, of course, just not a major focus among Chicago‐based startups. For example, scheduling tools are abundant in the industry but there doesn’t appear to be any local, Chicago‐based startups focused on that currently. Others remain “white space” opportunities, however, due to the nature of the problem to be solved. For example, things like Quality Assurance, Labor Marketplaces, and Supply Chain Management are hard problems to solve with software alone.

Interestingly, I’ve had multiple conversations recently with founders who currently reside outside of Chicago but are considering moving their companies to Chicago. While those conversations were completely unrelated to the above list, they corroborate the fact that there are still “white space” opportunities in the Chicago market.

C. Grouped By “Sector” / Market / Vertical

Upon discovering that the dataset includes more than just startups (e.g., various IT consulting

firms or other technical services providers), we decided to further break out the companies by “Sector”

to better understand the composition—instead of removing them from the dataset. This section of the

report will describe those Sectors or verticals and attempt to draw additional insights or observations.

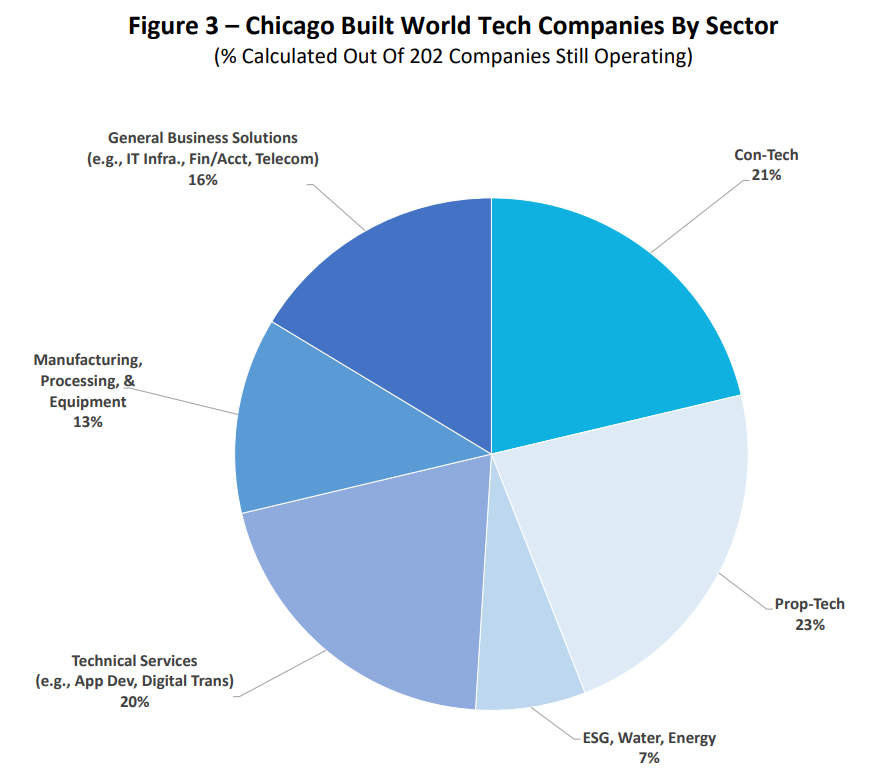

Figure 3 below summarizes how the 200+ companies break down by “Sector.”

The above breakdown highlighted two immediate takeaways. First, as is the case for Chicago

generally, the technology companies in the dataset are highly diversified since there is not one

dominant theme necessarily. Second, the number of technical services providers (e.g., custom software

development, digital transformation, etc.) and general business solutions (e.g., telecommunications, IT

infrastructure, etc.) also supports the earlier point that Chicago’s B2B technology market is strong.

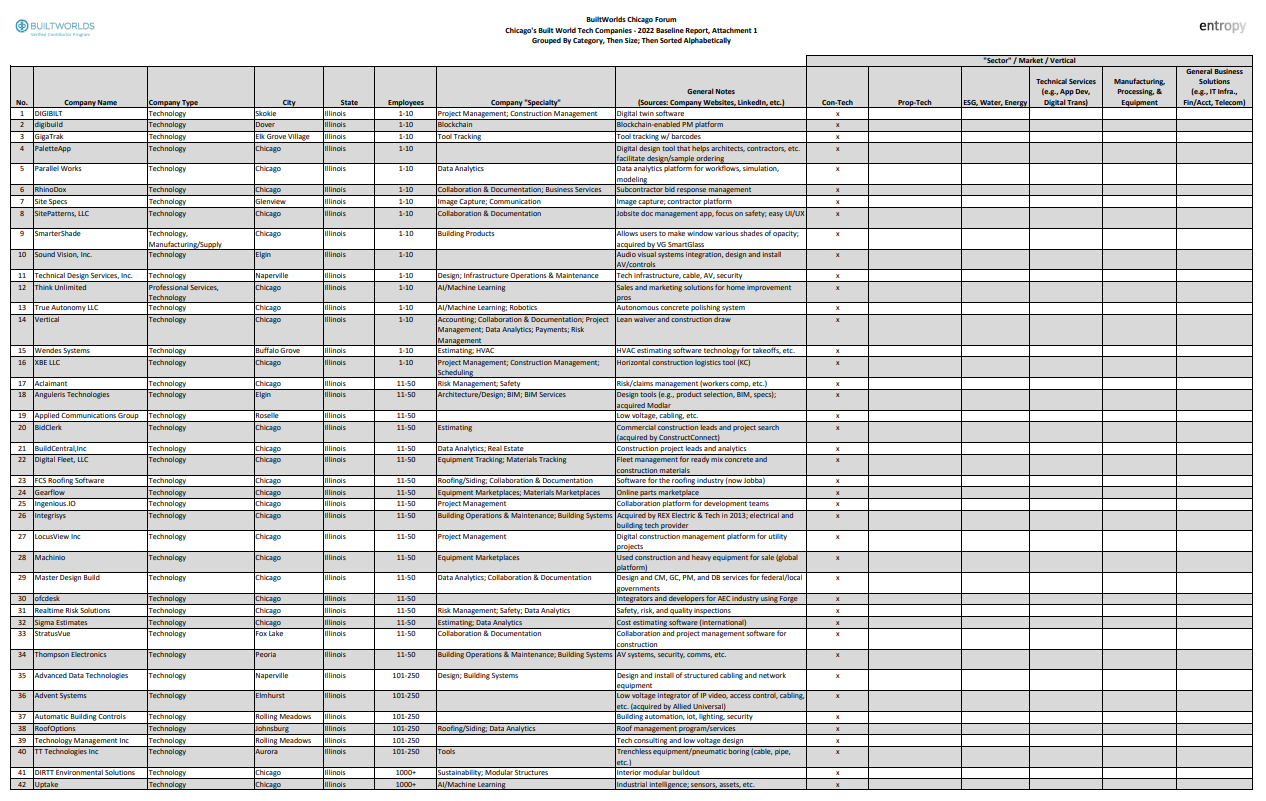

1. Construction Tech

Companies categorized as construction technology (or “con‐tech”) represent approximately 21%

of companies in the dataset that are still operating (43 of 202 companies). These companies generally

include Specialties related to the delivery of projects from initiation to completion. For example, things like identifying new project leads, estimating, project management or construction management

platforms, tool tracking, equipment marketplaces, onsite installation, risk management, logistics, and

several others are included in this category. Among the more recognizable names in this category are:

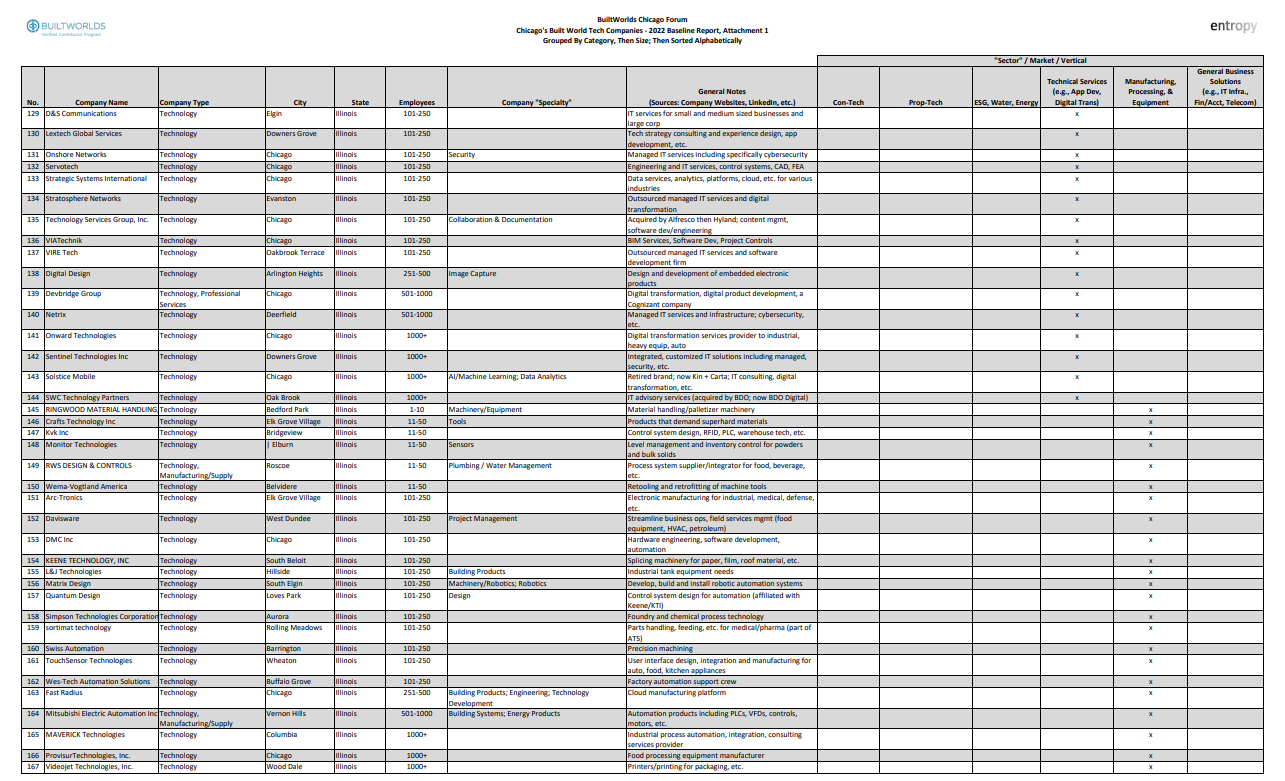

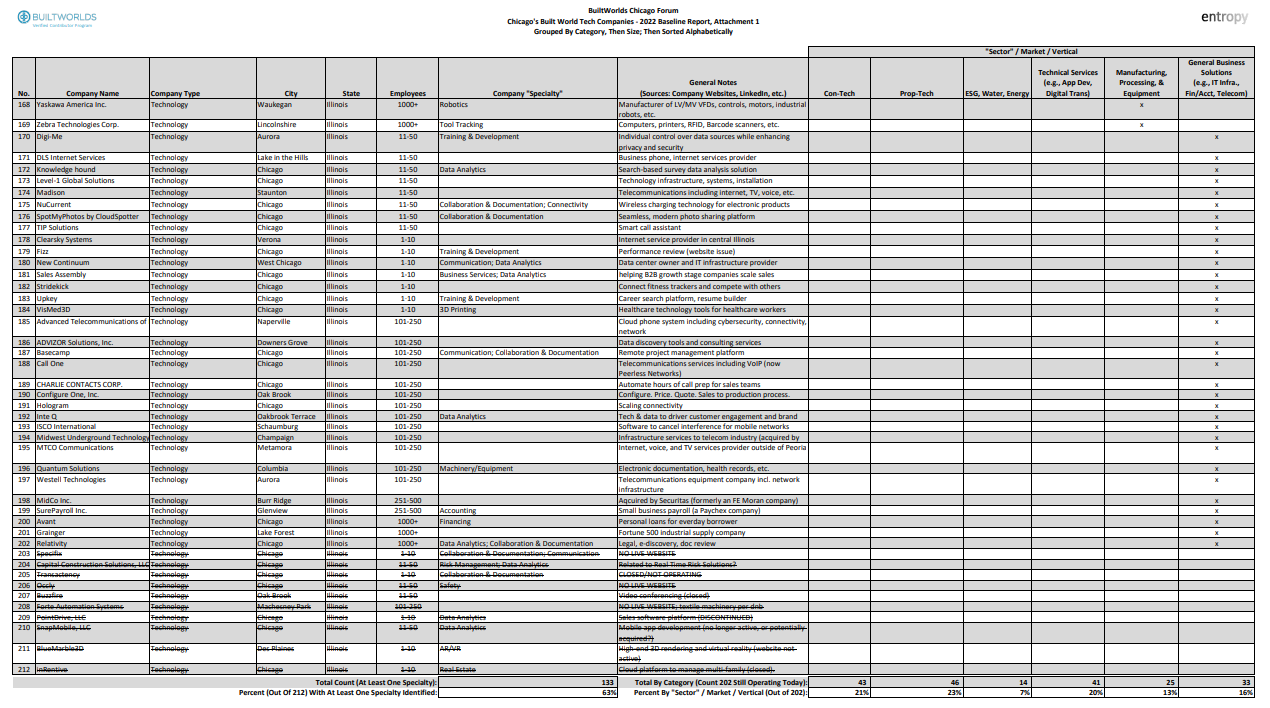

The full list of con‐tech companies can be found in Attachment 1, rows 1‐43. Note: Attachment

1 is grouped by Sector (i.e., all “con‐tech” companies are shown at the top, followed by “prop‐tech” and

so on). Within each sector, the companies are sorted first by company size (i.e., smallest companies with 1‐10 employees at the top, then 11‐50, then 51‐100, and so on). Finally, within each employee count grouping (i.e., within the 1‐10 employees range), the companies are sorted alphabetically.

2. Property Tech

Companies categorized as property technology (or “prop‐tech”) represent approximately 23% of

the companies in the dataset (46 of 202 companies). These companies generally include Specialties

related to the development, operation, or maintenance of property or other fixed assets. For example,

things like real estate planning, generative design, augmented or virtual reality, image capture including

drones for surveying, building operations and maintenance, smart cities, mobility, and several others are included in this category. A few of the more recognizable names in this category include:

The full list of prop‐tech companies can be found in Attachment 1, rows 44‐89.

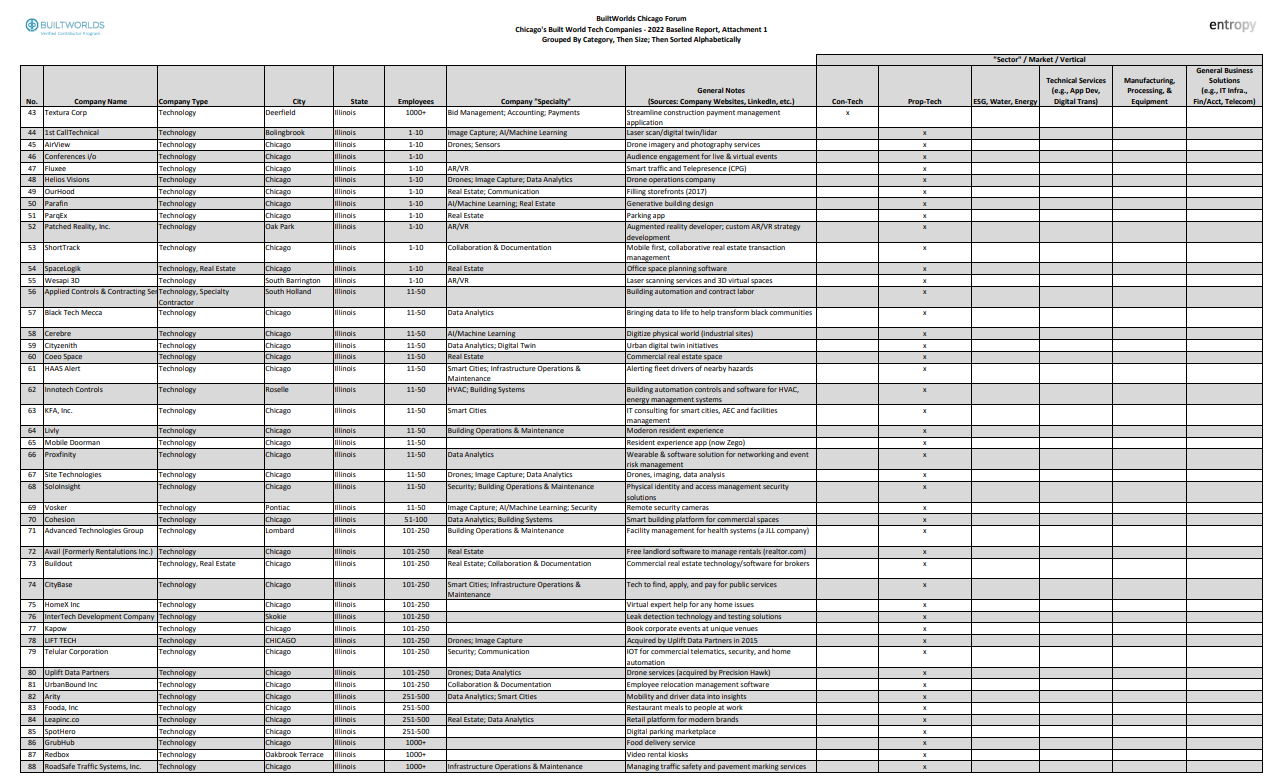

3. Environmental, Social & Governance (“ESG”), Water, & Energy

Companies categorized as ESG, Water & Energy represent approximately 7% of the companies in the dataset (14 of 202 companies). These companies generally include specialties related to environmentally conscious technology products or services. For example, things like clean water, energy generation and storage, sustainability, renewables, circular economy, eliminating waste, and others are included in this category. A few of the companies in this category include:

The full list of ESG, Water & Energy companies can be found in Attachment 1, rows 90‐103.

4. Technical Services Providers

Companies categorized as Technical Service Providers represent approximately 20% of the companies in the dataset (41 of 202 companies). These companies generally include Specialties related to data analytics and software development. For example, things like data center management, digital transformation services, custom software or app development, network consulting services, workflow automation, technical project management services, and others are included in this category. The full list of technical service providers can be found in Attachment 1, rows 104 to 144.

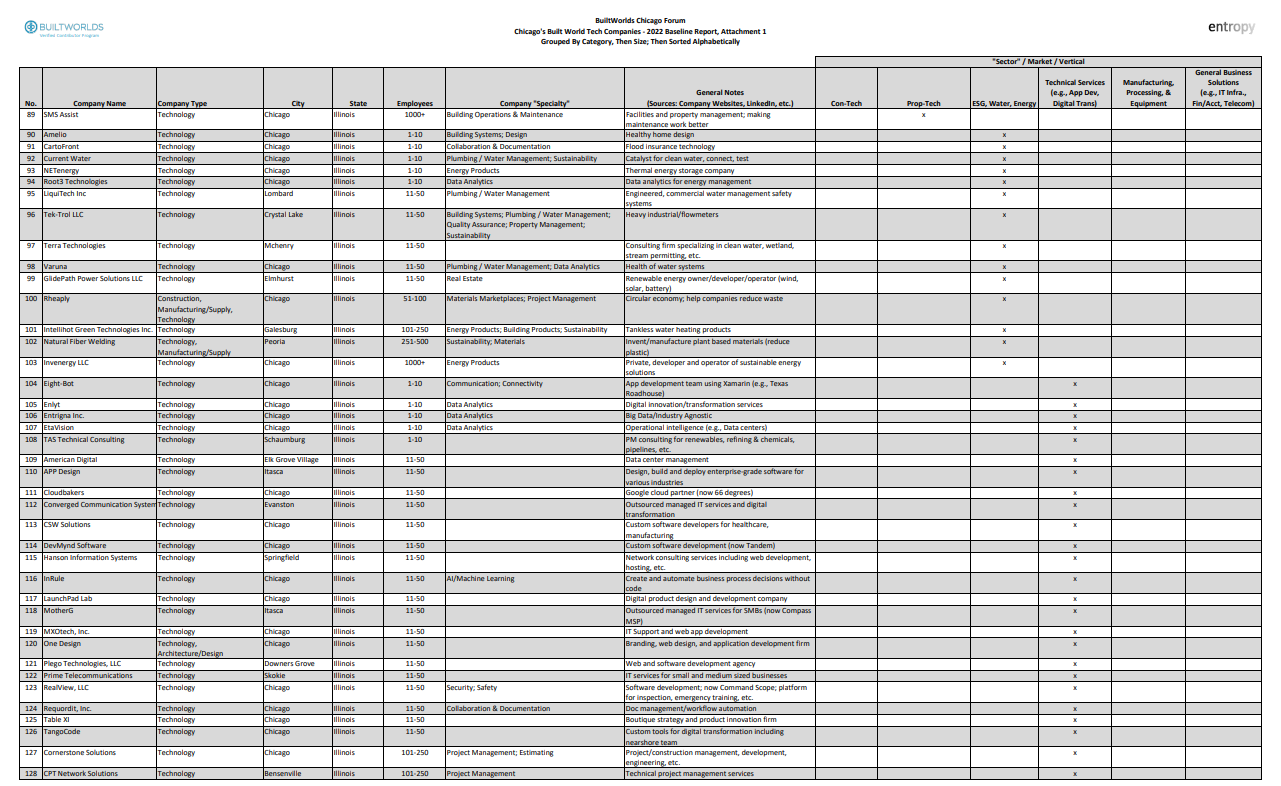

5. Manufacturing, Processing, and Equipment

Companies categorized as Manufacturing, Processing, and Equipment represent approximately 13% of the companies in the dataset (25 of 202 companies). These companies generally include Specialties related to machinery, equipment, robotics, and other automation systems. For example, things like parts and material handling, control systems, tooling, hardware engineering, and others are included in this category. The full list of manufacturing, processing, and equipment companies can be found in Attachment 1, rows 145 to 169.

6. General Business Solutions & Other Miscellaneous

Companies categorized as General Business Solutions and Other Miscellaneous represent approximately 16% of the companies in the dataset (33 of 202 companies). These companies generally include Specialties related to technology infrastructure—as well as other miscellaneous companies that did not fit in other sectors. For example, things like phone and internet providers, telecommunications equipment, owners of data centers, mobile networks, and others are included in this category. Also included are companies that offer a product or service to various industries, including construction and real estate (e.g., Relativity is a document management platform for the legal industry that is often used for construction lawsuits). The full list of general business solutions and other miscellaneous companies can be found in Attachment 1, rows 170 to 202.

IV. Looking Ahead / Where We Go From Here

This closing section will address three main areas. First is how to measure an entrepreneurial ecosystem. Second is identifying the various roles within the ecosystem that are available for people to get involved. Third is the unique opportunity that Chicago’s diverse built world ecosystem presents in the form of cross‐pollination and breakthrough ideas.

A. How Might We Measure An Entrepreneurial Ecosystem?

Whenever people talk about growth in business or measuring progress of a business initiative, Peter Drucker’s quote usually follows: “If you can’t measure it, you can’t improve it.” But what do we measure? Is it number of startups or tech companies, or total number of employees? The number of startups or tech companies is as straightforward as it gets…maybe too straightforward. We don’t just want quantity we also want quality. Quality companies and products—measured of course in the form of high returns and successful exits.

Interestingly, the broader Chicago entrepreneurial ecosystem faced a similar challenge early on and the result was a startup itself. As described in the HBS case, the on‐line tech community Built In Chicago was founded, in part, to measure the growth and development of the ecosystem. The founder of Built In Chicago, Matt Moog, said of the effort, “We quantified as much as we could to show the year over year successes and gave the mayor and government the needed talking points to publicly get behind this.” In other words, measuring entrepreneurial activity was borne out of the necessity to show the community leaders and public officials that these innovation efforts were in fact working.

The HBS case called attention to this same challenge with an excerpt from an article by the Kaufman Foundation, an organization focused on advancing entrepreneurship, improving education, and supporting civic development in the Kansas City area. Here’s the excerpt: How do you measure your entrepreneurial ecosystem?

How should you interpret the data about your startup community? What economic indicators should matter for vibrancy and growth? These questions come up repeatedly in conversations with entrepreneurs, program heads, event organizers, investors, policymakers, and others. The frequency of these queries reflects the phenomenon: With the rapid spread of efforts to build entrepreneurial ecosystems, it’s only natural to wonder what outcomesshould be tracked. And, what you track depends on what you’re trying to achieve.” [Emphasis added]

– Kauffman Foundation, 2015

It might be worth having a discussion amongst Chicago Forum members regarding what we’re trying to achieve, both individually and as a group—and brainstorm how best to align those incentives. Examples of potential measurements include the following:

- Financial Capital (e.g., revenue, equity capital raised, number of exits)

- Human Capital (e.g., jobs created, average number of people employed)

- Intellectual Capital (e.g., number of patents or other R&D outputs)

- Social Capital (e.g., mentorships, network connections, referrals)

- Cultural Capital (e.g., university case studies, major awards, media mentions)10

Entrepreneurial ecosystems are not a zero‐sum game. In fact, when the right mix of people come together voluntarily and in the spirit of cooperation, it’s almost always a positive‐sum game as evidenced by the above categories of measurement

B. What Are The Various Roles Within The Ecosystem?

The primary focus of this report is technology companies. But anyone whose spent any time in an entrepreneurial or startup environment knows that it takes more than just technology companies to grow an ecosystem—especially in a B2B environment like Chicago. The purpose of this section is not to do a deep dive into the other pieces of the puzzle. But instead to identify them and simply acknowledge

the important role they play in the ecosystem.

Select examples include venture capital firms and AECO players. While we won’t get into detail regarding either of these groups in this report, we may highlight them in future reports and meetings. Other important pieces include local universities and government agencies responsible for economic development. While neither would be expected to lead efforts to grow the ecosystem, they can provide support in various ways obviously.

The other piece of good news is in a big city like Chicago many of these other roles are well established, and so there’s no sense in recreating the wheel—it’s often just a matter of convening the right people, looking for ways to help each other out, and finding alignment with other organizations whose mission is similar but also not overlapping. For instance, as those who attended the first Chicago Forum meeting know, there is potential to collaborate with groups like P33 Chicago, a local non‐profit chaired by Penny Pritzker, Chris Gladwin, and Kelly Welsh that is doing incredible work for underrepresented tech founders. For those who weren’t in attendance, at our first meeting, CEO Brad Henderson gave a keynote talking about, among other things, retaining talent in Chicago and various other initiatives. Here’s a link to the P33 Velocity report that covers some of the same topics. Also, at our second meeting, Evan Shy from P33 shared some more details regarding P33’s TechRise competition where it awards $25K every week to an aspiring entrepreneur.

C. “There’s Magic In Cross‐Pollination”

The above quote is from a book titled, The Ten Faces of Innovation, by Tom Kelley of IDEO. IDEO, for those who are not familiar, is a design consultancy involved in some of the early Apple products, among many other notable brands. The book essentially presents ten personas that are critical to the success of IDEO’s diverse teams—the “Cross‐Pollinator” is one of those personas. Cross‐pollinators on IDEO teams, for example, are known for taking companies on “field trips to visit and

observe analogous operations far outside their own domain.” In this section, we’re going to float some ideas for how we might leverage Chicago’s diverse built world tech ecosystem by doing our own version

of cross‐pollination.

Examples of cross‐pollination in business are innumerable. A construction related example is the concept of reinforced concrete which was “created by a French gardener to strengthen flowerpots” reportedly before it was adopted by civil engineers and architects who extended the gardener’s concept to various structures. What’s the point? Well, there is no better environment to cross‐pollinate than a diversified economy. I won’t get into detail here regarding how best to go about that—we can leave that for future meetings. However, I will offer the following as possible examples of cross‐pollinating:

- Inviting speakers from outside our domain to Chicago Forum meetings

- Asking questions like, what might construction finance professionals learn from Avant?

- Reverse mentoring – invite speakers from younger generation to inform and inspire

- Invite a non‐construction group to a meeting; present them with a construction problem

In other words, have fun with the idea of growing an entrepreneurial ecosystem. And maybe break some of the traditional rules and take risks we might not otherwise take in our day jobs—with the hope that maybe we’ll inspire the next breakthrough idea…or the next five, ten, or fifteen breakthrough ideas within the Chicago built world tech ecosystem.

Burnham’s plan for Chicago came to be realized to a large degree—and it was no small feat to bring it to life. And, thanks to that high quality planning and execution, now seemingly countless great companies, small and large, call it home. Burnham and others didn’t just build Chicago for the people living there at the time either—they built it with the goal of expansion and future growth. In fact, it was hardly a goal…it was an expectation. So, in that spirit, and in the words of Burnham himself, let us, the next generation of planners, builders, and technologists, “make no little plans...”

Author Bio:

Dave Hettinger is the Founder & Principal of Entropy. He spent the first 15 years of his career analyzing problem projects—helping owners and contractors recover from cost overruns and schedule delays. He was fortunate during that time to learn from experiences with Fortune Global 500 corporations, including several multinationals, over half of the top 20 contractors, and many of the top owners, architects, engineers, GCs, subcontractors, construction attorneys, and consulting experts in the

industry—on over 100 different projects. He started Entropy to help those same clients leverage their data and technology to prevent problem projects, for the benefit of the industry as a whole—and he also assists built world startups in the risk management space with product design and development.

Footnotes:

1 The process to identify “Technology” companies in the greater Chicago area was an iterative one. The team tried

to be precise in our accounting of company data; however, it is possible that certain companies were missed

inadvertently or may have grown or pivoted since the data was compiled. So, to the extent you work for a Chicago

built world tech company and believe you were either not properly accounted for or miscategorized in this report,

please simply email research@builtworlds.com with any updates.

2 https://www.startupgrind.com/blog/chicagos‐1871‐tech‐incubator‐a‐model‐for‐innovation/

3 “Chicago Innovations That Changed The World”, James Janega, Chicago Tribune, January 4, 2014. Note: Michael

Jordan was not listed in the 2014 Tribune article. I added that under the assumption all Chicagoans would agree

4 This is a reference to the book by Nassim Nicholas Taleb, titled Black Swan, originally published in 2007. The

book focuses on the extreme impact of highly improbable, unpredictable, or outlier events (e.g., 2008 housing

crisis, 9/11 terrorist attacks, or COVID‐19 global pandemic). Highly recommend it.

5 For example, in the second meeting of the Chicago Forum, members discussed the possibility of expanding the

report to include major Midwest metropolitan areas within a certain radius of Chicago (e.g., Milwaukee).

6 There were a significant enough number of technical services firms and firms in adjacent industries. Therefore, it

made sense to break those out as part of the effort to group by “sector” / market / vertical (Section III.C).

Companies no longer operating appeared to be minimal (i.e., approximately 10 companies, or 5% of the total).

7 Some of the larger companies (i.e., 251+ employees) may operate in adjacent industries as opposed to purely

“built world” companies. Also, in certain instances, the team attempted to update this chart based on growth in

headcount since being added to the database (e.g., Ingenious.build was 11‐50 when first added, but is now

between 51‐250 employees).

8 Initially, the team considered filling in the remaining one‐third of company specialties. However, this would’ve

been very subjective since companies could select more than one Specialty. Therefore, that step was considered

but not taken at this time.

9 Since this analysis focused exclusively on Illinois‐based companies, technology firms based in other cities that are

present in the Chicago market were not part of the analysis (e.g., Procore is widely used by Chicago AECO players,

but itself is not based in Chicago and is therefore not in the dataset).

10 Endeavor’s Impact Scorecard from 2015, mentioned in the HBS case. Endeavor is a New York‐based, non‐profit

organization whose mission is “to mobilize private sector, university and community partnerships to catalyze high

impact entrepreneurship as a tool for economic development.”