by DAVID WALLANCE, AIA, LEED AP BD+C / FXFOWLE Architects | Feb 22, 2015

A panel of experts recently convened at the Center for Architecture/AIANY to address the question: Can innovative project delivery methods, namely modular construction, bring down costs and offer a solution for housing in New York City?

It’s not, in fact, a new question, but it could not be timelier. The construction industry has, according to one study, seen a 15% decline in productivity over the last 50 years, in sharp contrast to all other non-farm industries that have seen an increase of 250% over the same period. The problems that afflict construction, which bear directly on productivity and therefore on cost, have been written about and discussed for years, if not decades. In the face of these trends, developers, architects, and construction managers are mainly passive participants who adapt, project by project, to budget constraints that are driven by forces occurring at a macro-economic level.

Despite advances in information technology, new materials and methods, and new project management techniques, the construction site remains essentially the same as it has been for thousands of years. A workforce dispersed in a three-dimensional workplace, using hand-held tools, assembles pieces and parts according to a unique set of instructions that they are following for the first time. The work is done in the heat and cold, under rain and snow. The building trades jealously guard their jurisdictions, and often owe more allegiance to the union than to the subcontractor. Building technology, building codes, and building designs are ever more complex.

In 2013, Forest City Ratner (FCR) began construction at the Atlantic Yards in Brooklyn on a 34-story modular residential tower designed by SHoP Architects and manufactured by Skanska and FCR in joint venture.

As nearly everyone in the New York design and construction community knows by now, construction proceeded slowly and was halted several months ago (it has since resumed) after problems in the factory and at the site were leading to significant cost and schedule overruns. The Atlantic Yards project was seen as a harbinger of a new era in which modular construction would “crack the code” of cost, and the shutdown was a setback for many who had believed that modular high-rise construction was on its way.

“The Atlantic Yards project was seen as a harbinger of a new era in which modular construction would “crack the code” of cost, and the shutdown was a setback for many who had believed that modular high-rise construction was on its way.”

The panel at the Center brought some good news and fresh thinking, along with a dose of bracing realism. Stephen Kieran, with his partner James Timberlake, have long advocated for a shift from archaic design studio and construction trade practices to a model based on advanced manufacturing methods used in the automotive, aerospace and shipbuilding industries. Kieran’s presentation of his firm’s Loblolly House showcased the real-world application of modern industrial supply chain principles that were at the heart of Kieran’s and Timberlake’s book, Refabricating Architecture.

Jeffrey M. Brown, a developer and builder, presented The Stack, designed by Gluck +, a seven-story modular apartment building in Inwood, NY. Manufactured in Pennsylvania, trucked to Manhattan, it was stacked up in less than three weeks – although façade installation and interior fit-out continued for another 19 months.

Jim Garrison of Garrison Architects talked about a pod hotel project that he’s working on which will be manufactured in Poland and shipped overseas to New York – more cheaply than if it had been trucked from a modular plant in Indiana.

Modular obstacles

When my turn came, I had an opportunity to share some ideas that I’ve been working on for awhile now. First, I wanted to be realistic about the prospects for modular, given the current state of the industry. That was a bit of a downer. The legacy manufacturers, of which there are about a half-dozen that serve the New York market, have a comfortable business cranking out construction field offices and temporary classroom modules. They are more like “Mom & Pop” operations than like a large industrial operation. Bring them a set of drawings for an architect-designed NYC apartment building and you can expect to spend the next several months camped out on the factory floor, monitoring the work on a daily basis – which is exactly what Jeff Brown’s design team did. It worked for The Stack, but it’s not a scalable model.

The most important point about those “Mom & Pop” companies, though, is that they’ve imprisoned themselves in what I call the transportation fallacy. In striving to build the largest possible modules, believing that fewer trips down the highway, fewer crane picks, and fewer seams to zip up the field is the economical way to go, the legacy manufacturers have burdened themselves with high transportation costs and regulatory barriers. As a consequence, they are unable to compete with conventional construction beyond a 300-mile radius of trucking. Even within that limited geographic range, they rarely compete on cost savings – instead, they compete on time savings alone. The combination of high overhead, high local labor costs and limited market opportunity makes these companies vulnerable to the ups and downs of the business cycle, and therefore reluctant to invest in plant and equipment.

Like stunted trees on an exposed mountainside they expend all their resources on survival and cannot grow.

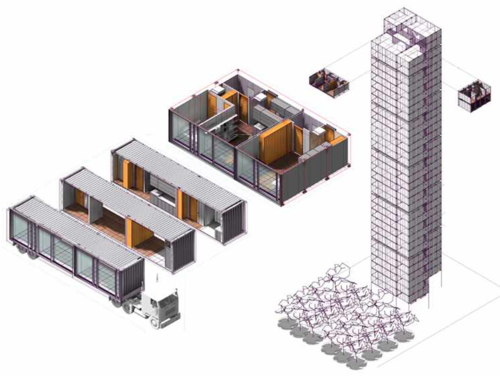

The key to unlocking the transportation fallacy is hiding in plain sight: the standard ISO shipping container, developed more than a half-century ago. The shipping container is a cheaply transported modular structure that is the basis of our modern global supply chain, moving seamlessly across oceans, rails and highways. In our work for Global Building Modules, Inc., we re-designed and re-engineered that standard container for optimal performance and interconnectivity as a high-rise building module, and we renamed it a Volumetric Unit of Construction, or VUC.

Final thoughts

We architects tend to view the design of each individual building as our field of operation, rather than thinking about a comprehensive and long-range approach for delivering lots of buildings. We are confined in our own organizational silos by the pressures of marketing and business development. Modular design and construction, if it is to succeed, will have to become a collaborative project.

We aren’t in the habit of thinking about design and construction the way, say, an MBA student might analyze a business case study, but maybe we need to broaden our outlook. We need to learn how to navigate the unfamiliar terrain of industrial processes, product design, business and marketing strategies, capital formation, supply chain logistics, and labor relations. We don’t need to become experts in these areas, but in the same way that we know how to talk to our consultants in the engineering disciplines, we need to develop the language and skills for dealing with experts in industrial enterprise.

The good news is that, judging by the attendance at this program event and by the high level of discussion among the panel and questions from the audience, the New York design community is engaged and ready for a new approach.

The author joined FXFOWLE in 2014 as Senior Associate after more than thirty years in practice, during which he has pursued an approach to design characterized by a synthesis of form and building technology. He believes that the public intuitively responds to buildings that are well-made, in which an architectural intention is legible at every scale, down to the smallest detail.

This article first appeared Feb. 10 on the FXFOWLE Blog.

Discussion

Be the first to leave a comment.

You must be a member of the BuiltWorlds community to join the discussion.