This is part 2 of a 4-part series by Walker Thisted, BuiltWorlds producer and resident architect, when he visited New York last month for the fifth annual Architizer A+ Awards.While he was there, he caught up with some members of the BuiltWorlds network, in addition to other innovative architecture firms in the industry.

After several decades of creating some of the most compelling buildings and urban plans in the United States, OMA New York — under the leadership of Shohei Shigematsu — is considering what kind of firm they want to become and how they want to distinguish themselves from the Koolhaas era.

Observation of existing site conditions, the needs of their clients, user culture, and the broader zeitgeist has made up the core of their past work and led to architectural tactics that define the approach to each project. This will likely remain unchanged as the firm evolves. However, the tactics and approach might become less radical and provocative than in projects past, as they consider their context in a subtler manner and incorporate historical conditions that might not have occurred when approaching the site as a tabula rasa or building within the context of critical regionalism.

The studio is exploring this evolving identity through recently completed projects such as the Pierre Lassonde Pavilion at the Musée National des Beaux-Arts du Québec and the Faena District in Miami. Both projects are concerned with creating a compelling place that fosters and supports a particular community while also exhibiting a design that carefully integrates the building with the site on which it sits.

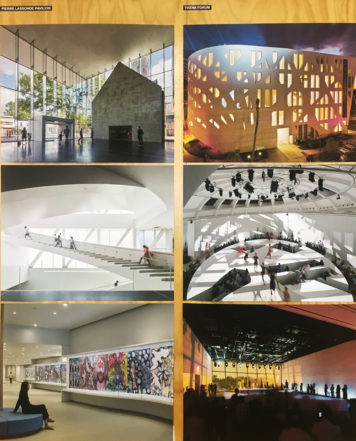

The Lassonde Pavilion

In the case of the Lassonde Pavilion, the building responds to the surrounding topography via a series of stepped volumes following the gradual incline of the hill rising from a lake. This ultimately creates a cantilevered space enclosed by glass as a subtle transition from life on the street to life in the Pavilion.

The incorporation of the volume of a gothic church building to the northeast helps to negotiate the past and future scale of the site. By introducing a circulation strategy that begins with a twisting staircase, the visitor is given the opportunity to experience multiple angles of the building through a circular pattern of motion.

This pattern is interrupted by an externalized volume containing a linear staircase connecting the second and third floors of the Pavilion. This reconnects the visitor with the exterior context while simultaneously allows those outside to glimpse what is occurring inside a building whose primary facades remain translucent, allowing light to pass through and the structural system to emerge.

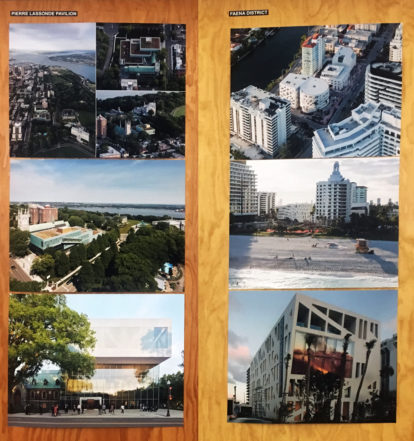

The Faena District

The Faena District — a six-block project that includes a 169-room hotel, a 50-room hotel, three condominium buildings, a cultural center, and a retail complex — considered a very different strategy when siting the building.

Living amongst white concrete buildings between the ocean and the Indian Creek Waterway, OMA’s work is comprised of the Faena Forum, a cultural space accommodating performances and exhibits, the Faena Bazaar, a shopping space accommodating retails, and Faena Park, a garage accommodating visitors of the Bazaar and Forum.

The buildings fit within their context by drawing on the plasticity of the surrounding largely white concrete forms. A rectilinear strategy is used for the Park and Bazaar, but a mixed circular and rectilinear volumetric strategy is used for the Forum. Each uses the surface of the building to express their respective identity.

A large underground parking plane connects the three buildings and penetrates the surface via Faena Park. The parking structure uses car lifts, highlighted via a transparent surface, to articulate the building form and provide a break from the punctured circular surface providing a formal link to the Forum.

Faena Forum

In the case of the Forum, the exterior is reminiscent of some of the Constructivist structures that inspired OMA’s early work and also offers a connection to the sprouting form of the surrounding palm trees.

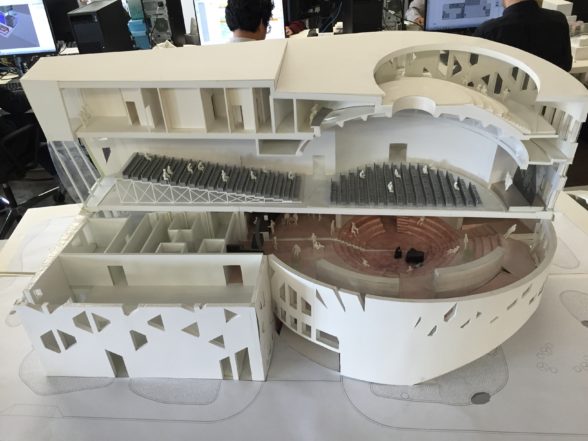

As was the case with the Lassonde Pavilion, the building volume creates a covered space that mediates between public space and the programmed space of the Forum. This protected space is created by carving directly from the circular volume rather than by cantilevering a pure form.

The Constructivist inspiration continues within the interior of the Forum, as the circulation spirals around the Lobby and Assembly Hall and ultimately rises to an oculus held in place by a spiral pattern reminiscent of Tatlin’s Tower of Babel or Borromini’s St. Ivo. As the visitor moves through the space, they are given the opportunity to come into close contact with the structural forms of the dome as they move through an interstitial space between the domed Assembly Hall, before ultimately arriving at the top and looking back down at the Hall’s floor below.

This rather Baroque move creates unexpected opportunities to encounter other visitors and see the building from a variety of angles. It also fits well in the broader decision to connect a circular volume with a rectangular volume caste at a slight angle, creating an almost awkward marriage as a result that infuses the building with dynamic motion.

The Forum, in this sense, blends a Greek or Republican Roman model with a space such as the Imperial Roman Pantheon in order to create a cohesive building supporting the exploratory motion of visitors and moments of stasis as they watch others spring into motion to perform a work of art.

The future of OMA

Both the Faena District and Pierre Lassonde Pavilion incorporate complex programs, forms, textures, and circulation paths that reveal the building and their surroundings in a way that is reminiscent of past projects by OMA. Although both are cultural projects designed to bring communities together around the experience of art, the Lassonde Pavilion is primarily focused on visual art; the Faena forum is focused on the performing arts.

The buildings that OMA New York has underway are complimented by research initiatives both in the office and beyond. Shigematsu’s research in the area of alimentary design conducted in coordination with his students at The Harvard Graduate School of Design offers insight into how he might position OMA’s future work both within the city and in architectural history.

Whereas Koolhaas used his tenure at Harvard to deeply investigate the history of shopping and its impact on urban planning, design, and lifestyle, Shigematsu has used his tenure to consider “how and what we eat” impacts the design and functioning of cities. This shift in focus lets us consider how priorities have shifted, the growing role of online retail, the potential decline of shopping culture and neo-liberal globalism in general, and the rise of a desire for renewed human contact around experiences in an era that has seen a rise in online interaction.

How design can address greater urban needs

The focus on the role that urban farming might play in the production of local food sources offers an opportunity to consider the broader ecology in which an architectural intervention sits as well as the most basic element of food as a source of place making and community identity. This focus in turn allows for a connection to a growing discourse on resilience that ties the building to the global flow of energy, goods, products, and services in a rather different manner than was understood through the frame of neo-liberal globalism.

This shift from neo-liberal globalism to ecological urbanism has the potential to reframe the role of the human in the design process from the end consumer to one more engaged in the making and remaking of the environment through the need of cultivating food and eating.

Engaging this shift might allow for a broader exploration of the relationship between high and low density urban and rural contexts as cities become increasingly expensive and new generations seek alternatives. As this shift occurs, it is likely that OMA New York will continue to use tactics developed over the past 40 years.

While Koolhaas stretched the scope of architectural practice by considering psychological, political, and economic dimensions of design, Shigematsu will likely consider cultural practice, user experience, and food production and consumption within his scope to better understand how architecture and urbanism can address challenging global problems — from food deserts to crime and disinvestment, to overcrowding and energy shortages, to environmental change and political mismanagement.

Doing so will not shift OMA’s fundamental identity, but provide a bridge for these tactics to be refined.

Discussion

Be the first to leave a comment.

You must be a member of the BuiltWorlds community to join the discussion.