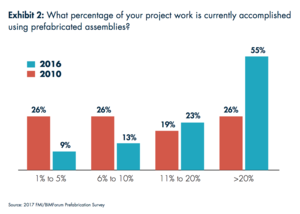

On Feb. 9, FMI issued one of its latest reports, “Prefabrication: The Changing Face of Engineering and Construction,” and the numbers presented within suggest that more and more building projects aren’t being put up simply beam by beam. Of the 156 contractors FMI surveyed for the report, 55 percent—compared to just 26 percent in 2010—estimated that prefabricated assemblies made up more than 20 percent of their work, and FMI also found that the actual amount of prefab work in the industry has nearly tripled, from 13 percent in 2010 to 35 percent last year.

Though it hasn’t come close to being the norm for the company yet, prefabrication has begun to creep into the work of structural engineering firm Thornton Tomasetti, according to vice chairman Aine Brazil, from the preassembly of smaller pieces off-site for some projects to construction of larger modules for a handful of projects such as the Stavros Niarchos Foundation–David Rockefeller River Campus at Rockefeller University. “What’s happening, I think, is people would really like to see buildings that could be made up of standard building blocks—kits of parts that you can just pull together and use,” she says.

Brazil believes prefabrication and modularization will continue to account for a growing amount of work moving forward, and as it does, she’s already seeing how it could change her and her firm’s engineering work in key ways. Below, using the Rockefeller University project as a case study, is a look at a four things Brazil thinks engineers will have to consider more closely.

Closer collaboration with contractors

Historically, the structural engineer of a project would be in charge of designing its frame, making sure each portion of the structure can handle the different loads and stresses placed upon it while making room for piping, conduits, and other components. Then, the contractor would take over for the actual construction of the frame and its components. Maintaining this separation of duties is difficult when working with prefabricated or modular parts, however, because it’s no longer enough “to design something that will work for the final condition,” Brazil says.

In the case of Rockefeller University’s river campus, consisting of a new building stretching over FDR Drive to connect the school to the East River, the 19 modules of the steel superstructure that Thornton Tomasetti and the rest of the design-bid-build team eventually settled on were massive, approximately 90 by 48 feet and weighing more than a million pounds each. These modules needed to have “total stability in and of themselves,” Brazil says, but Thornton Tomasetti couldn’t immediately know how they would handle the stresses imposed by the rigging system that subcontractor Banker Steel designed and attached to a barge crane hook to hoist the modules into place.

“Turner Construction and Banker Steel figured out the actual pieces they’re going to lift, everything about their center of gravity, how they’re going to be loaded,” Brazil says. “They actually have an erection engineer in-house that does a certain amount of the analysis, and we collaborate with him, we check what he does, we talk, we question. It’s a process of getting to an endgame that works for both of us.”

In essence, when working with prefabricated parts, it’s not enough to engineer the building itself; the construction process must be more carefully engineered as well, and that will entail more communication between the engineer and the contractor. FMI’s report notes this, too, stating, “As this ideological and structural shift in the construction industry continues to evolve, we will likely witness a move from traditional design-bid-build contracts toward design-build and new forms of integrated project delivery.”

A focus on custom repeatability

Building a suburban house from factory-made component parts is one thing, but the more complicated a construction project gets, the more difficult it is to rely on the uniformity of prefabrication and modularization, especially for structural engineers, who have to account for complications such as varying wind stresses from the top few floors to the lower floors of high-rises. “Every building has some uniqueness to it,” Brazil says. “That doesn’t mean you can’t do modules. … They [just] need to be a little more customized.”

For Rockefeller University’s river campus, for example, the distance across FDR Drive actually varied from one end of the three-story structure to the other, meaning it needed to go from approximately 88 feet wide in some sections to 93 feet wide in others. Thornton Tomasetti kept the design of its steel-frame modules flexible enough to accommodate the varying widths, but it was still able to incorporate comparable, sometimes identical details and components into each one. “There were enough significant similarities that we were able to develop a consistency of approach, and that becomes pretty important,” Brazil says.

“Every building has some uniqueness to it. That doesn’t mean you can’t do modules. … They [just] need to be a little more customized.”

New scheduling considerations

FMI’s survey participants ranked “reducing time to project completion” as the number one benefit of prefabrication and modularization. The ability to assemble large portions of a project off-site and simply drop them into place means far less time spent on the job site, and Brazil says this was actually a huge help in completing Rockefeller University’s river campus project according to a strict timetable.

Thornton Tomasetti and the rest of the project team learned that the quietest period along their site’s stretch of FDR Drive was June through early August, and a modular build allowed them to propose a completion date before activity would return nearby at the United Nations in September. “It was a real benefit to the city for us to do it in the summer,” Brazil says, but she adds that the city only approved the lifting of modules over a closed FDR Drive for a certain number of nights. “We developed details … so that you could swing in [each module] and sit it into position and make a sufficiently rigid connection so that you have stability and safety and can open the FDR Drive by 5 o’clock in the morning.”

New siting considerations

Though prefabricated and modularized components are likely to become more popular in the future, Brazil thinks site selection will have a big influence on their size and whether they’re used at all for particular projects. “A sixty-foot-long piece of prefab can be transported into the city easy enough, and you can transport something that’s about 14 feet wide or 14 feet high,” she says. “But, that’s not that huge in terms of a room module. To bring those [larger] elements, you need to be able to ship them easily, and you need to find a place that has the crane space to lift them into place when you get them there.”

Luckily, the Rockefeller University project was situated right next to the East River. The pieces for it were fabricated by Banker Steel in Virginia, shipped to and assembled into larger modules in Keasbey, NJ, and transported by barge to a position next to Turner Construction’s barge crane floating adjacent to the site. For other projects Thornton Tomasetti is working on around the city, though, “a lot of them are being built in a similar manner to fifty years ago, … one piece at a time,” Brazil says.

She sees smaller modules being used for specific spaces such as bathrooms—or even just specific portions of rooms. “You might just prefabricate a headwall for a hospital bed, which is still complicated but just one piece,” she says. “Structural modules are best suited to repetitive building units like smaller apartments.”

Discussion

Be the first to leave a comment.

You must be a member of the BuiltWorlds community to join the discussion.