by ANDREW G. ROE, for BuiltWorlds | June 23, 2015

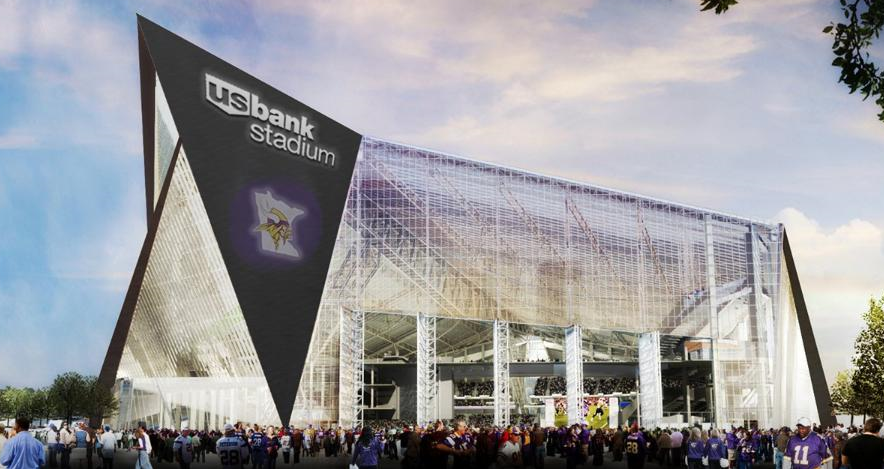

When the Minnesota Vikings’ shimmering new U.S. Bank Stadium opens in 2016, the professional football team and its hardy fans hope the $1-billion facility will capture the best of both worlds: an indoor stadium with an outdoor feel.

With a largely transparent roof, glass-laden walls, and 95-ft-high glass doors that open to downtown Minneapolis, the Vikings’ new home is designed to connect occupants inside with the elements outside. Its angular combinations of steel, concrete, glass, and other materials, along with an aggressive schedule and a tight site, have led designers and builders to rely heavily on virtual design and construction (VDC) to keep the project on track for completion.

With up to 1,000 workers on-site at one time, the stadium’s general contractor, Minneapolis-based Mortenson Construction, says VDC has been the key to keeping the project on schedule. “We have 30 months to build something this large,” says Ricardo Khan, Mortenson’s director of integrated construction. “To coordinate all those people, we use the best resources we can to reduce waste.”

The team of six VDC personnel uses a variety of software tools, including Autodesk Revit for viewing models, Autodesk Navisworks to combine design and construction information for simulations, Synchro Software’s Synchro Pro to integrate scheduling and 3D models for 4D simulations, and various other tools as needed.

Lofty Design Challenges

Prior to breaking ground, Mortenson and the design team also leaned heavily on technology. Dallas-based architect HKS shared early Revit models with Mortenson for cost estimating and constructability reviews. “On a weekly basis, we would upload our model. Mortenson and their subcontractors would split out the pieces and give us feedback,” says architect Kevin Taylor, HKS project manager, who also helped design the Dallas Cowboys’ AT&T Stadium. HKS also designed Lucas Oil Stadium in Indianapolis, and Mosaic Stadium in Regina, Saskatchewan.

U.S. Bank Stadium’s design features a ship-like profile, with a 1,000-ft-long ridge beam running along the middle of the roof, pointing upward toward the Minneapolis skyline. Crews refer to this beam as the “prow,” a marine term for the forward-most part of a ship bow that cuts through water.

Winter is Coming: The transparent, nautical design evokes both an iceberg and an ark. (Images from HKS)

The design was also heavily influenced by Minnesota winters. “We wanted to react to the snow,” says Taylor. “It looks like an iceberg and… (its) roof is steeply sloped away from the ridge to move snow off the roof,” he adds. After it leaves the roof, gutters up to 50-ft wide and 50-ft deep carry the snowmelt to a storm sewer system.

With over half the roof transparent, “dealing with snow loads has been a challenge,” concedes John Aniol, structural engineer of record for Thornton Tomasetti in Dallas. To visualize the enormous task, the TT design team used Rhino from Seattle-based McNeel North America, and Grasshopper, a Rhino plug-in, to perform parametric modeling of the structural framework and optimize the roof slope. Steeper slopes can reduce snow loads, but at some point, they become impractical. “There was a sweet spot to lofting the roof,” says Aniol.

The adopted design employs a 14-degree slope on the north side of the ridge and a 17-degree slope on the south side. That southerly exterior is covered with transparent ethylene tetrafluoroethylene (ETFE) panels, which were also used on the Allianz Arena in Munich and Forsyth Barr Stadium in Dunedin, New Zealand. The north side is covered with a traditional steel deck and membrane. While the ETFE will cover roughly half the field, the angle of the roof will allow sunlight over the entire field.

The roof structure also includes 12 queen’s post trusses — six on either side of the ridge — spanning from the ridge beam to the concrete ring beam atop the stadium’s exterior. Grade 65 steel from ArcelorMittal, Luxembourg, was used to reduce truss weights by over 25% when compared to conventional Grade 50 steel, according to Aniol. Even with the higher strength steel, the ridge truss employs some massive members — the largest a W36-x-853 beam with a 4.5-in-thick flange.

Glassy Look

On the glass-dominated west end of the stadium, five doors up to 95-ft high and 55-ft wide will pivot and open to a public plaza. Each hydraulically driven door will pivot on a single jamb, a system chosen instead of sliding doors to save space, notes Aniol.

The operable doors provided another opportunity for VDC simulation. Using Lumion from Netherlands-based Act-3D, Mortenson produced animations of the doors opening and closing, helping the “owner make a more informed decision,” recalls Nathan House, Mortenson’s integrated construction coordinator on the project.

The glass doors and surrounding glass walls also raised concerns from environmental advocates who fear birds will fly into the glass. Addition of fritted glass was considered earlier this year to deter birds, but deemed too expensive. Such an alteration also had the potential to delay the opening of the facility by a year. Now, a textured overlay to mitigate the problem is being considered, according to Michele Kelm-Helgen, chair of the Minnesota Sports Facilities Authority.

Logistical Challenges

With the 1.7-million-sf stadium occupying nearly twice the footprint area of its predecessor, the Metrodome, but occupying essentially the same site, Mortenson’s VDC team has been tapped often to resolve potential space conflicts. One big “eye-opener” occurred when the team discovered a steel build-up area would occupy the same location as the precast concrete contractor’s crane, says House. By moving the build-up areas in the model and adjusting the schedule, “we were able to change things a year ahead of time, instead of on short notice,” said House.

Other VDC accomplishments included detecting clashes with structural and mechanical work and maintaining clearance between bolts and door trusses. “About 75% of my time is spent on collision avoidance,” he adds.

Mortenson’s project superintendent Dave Mansell echoed the value of VDC, noting the project schedule featured over 20,000 activities and up to 18 cranes on the job site at one time. Just past the half-way point now, the ambitious project remains on schedule. “We haven’t had any significant issues,” says Mansell.

Of note, computer modeling was also used heavily in the steel detailing and fabrication. TT used modeling software from Finland-based Tekla Corp. for steel detailing, then exported the model to the steel fabricators. Traditionally, fabricators handle more of the detailing process, such as designing bolt holes. “This was a streamlined process that resulted in schedule and cost savings,” notes Anion.

Preparing for opening, honoring the TWin cities

As we enter the summer, all systems now appear ‘go’ for a 2016 completion, when the Vikings will move into the new 65,000-seat venue. Already, the Twin Cities can’t wait to show off the place, which has been funded about 50% by the City of Minneapolis and the State of Minnesota. So far, Minneapolis already has landed the 2018 NFL Super Bowl and the 2019 NCAA Men’s Basketball Finals and it has submitted a bid to host the College Football Playoff Championship Game in 2020.

From Day One, the regional significance of the job also has not been lost on the project workers. “I’ve never worked on anything this magnificent, and probably never will again,” says Mansell. Mortenson is self-performing most of the concrete work, and has over 200 people on site.

[Video was Removed by host.]

On June 5, some 1,200 workers and staff from Mortenson and Thor Construction, architect HKS, and owners Minnesota Sports Facilities Authority and the Vikings all celebrated the concrete “topping out”.

Of the roughly 250 subcontractors, over 90% are Minnesota-based companies. Even the Brookings, SD-based scoreboard maker Daktronics has committed to do its work at its Redwood Falls, MN, plant, in keeping with the state-based theme. The company is building 18 LED video displays, and a total of more than 25,000-sf of video displays.

For its part, the Vikings ownership certainly appreciates the results it is seeing from the largely local team, watching the virtual images come to life, and using technology to keep the project on schedule. “It’s a real testament to the workforce,” says Mark Wilf, Vikings president.

Meanwhile, Wilf and his colleagues are eager to move into the new digs. During construction, the team has been playing its home games outdoors at the University of Minnesota’s TCF Bank Stadium, a comfortable venue in September, but much less inviting in December. The new U.S. Bank Stadium portends to offer actual warmth. “It’s going to be an indoor building,” says Wilf. “But people are going to really get a sense of a lot of light coming in, a lot of openness.”

But not so much openness that they can’t feel their fingers and toes. Definitely a plus for faithful fans at any midwinter sporting event.

Based in Minneapolis, the writer is a civil engineer, editor and consultant who has contributed articles to ENR, Design-Build, and Cadalyst, among other publications. He is president of AGR Associates, and the author of Using Visual Basic with AutoCAD, published by Autodesk Press. Email him at agroe@agrassociates.com.

Discussion

Be the first to leave a comment.

You must be a member of the BuiltWorlds community to join the discussion.