This article was submitted as part of BuiltWorlds’ Verified Contributor Program.

Many in our industry sense that the momentum of designing and producing electric heavy equipment is building – I’m one of them. At industry tradeshows, many OEM exhibitors are displaying electric equipment as an alternative to their diesel-powered models.

With more and more electric heavy equipment making its way to market, a lot of contractors in our industry wonder how far it’ll go and how fast. Government entities in particular have a need to better understand the timeline of machine electrification, including incentives and streamlined purchase processes as they work to keep their fleets compliant.

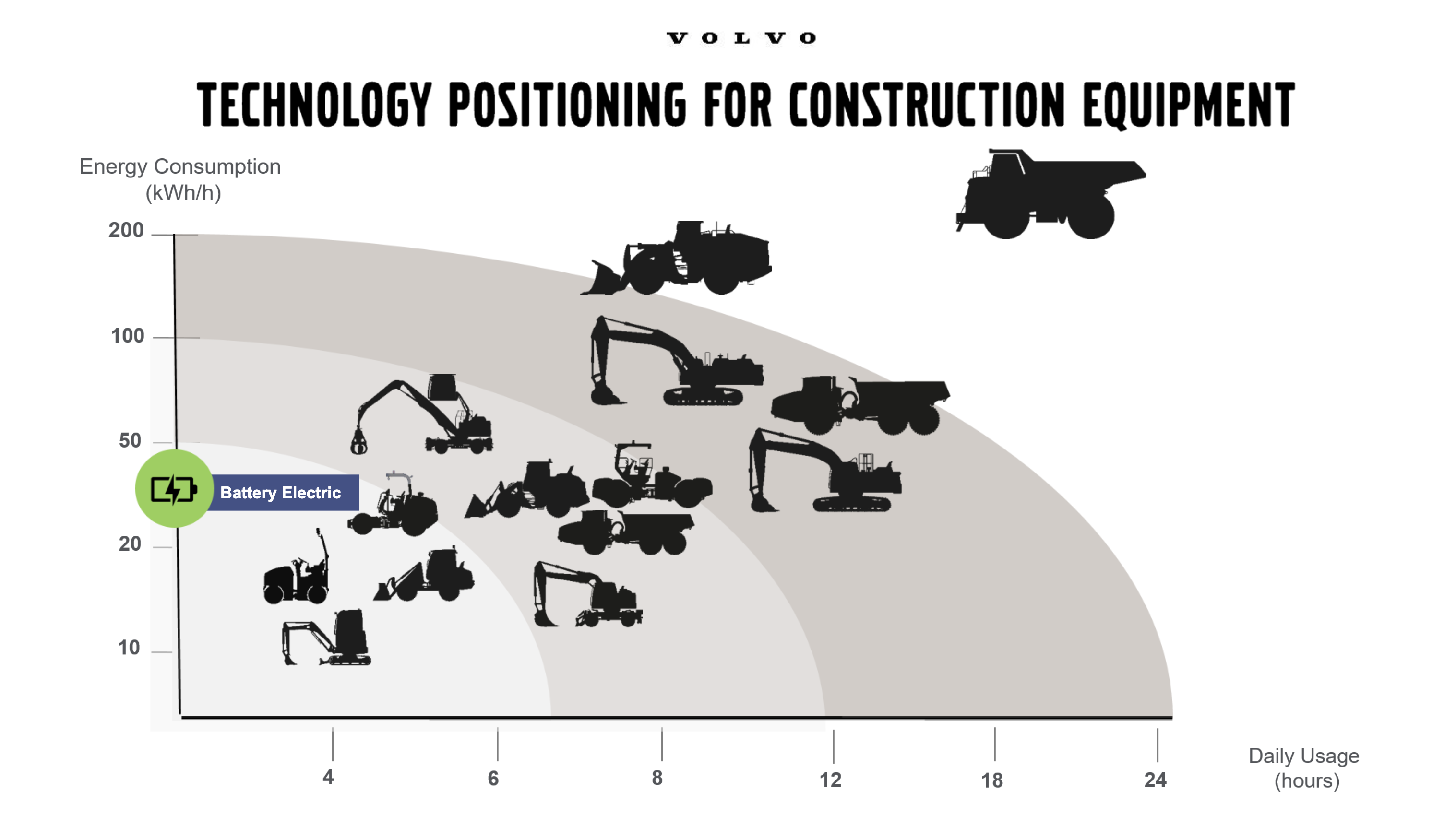

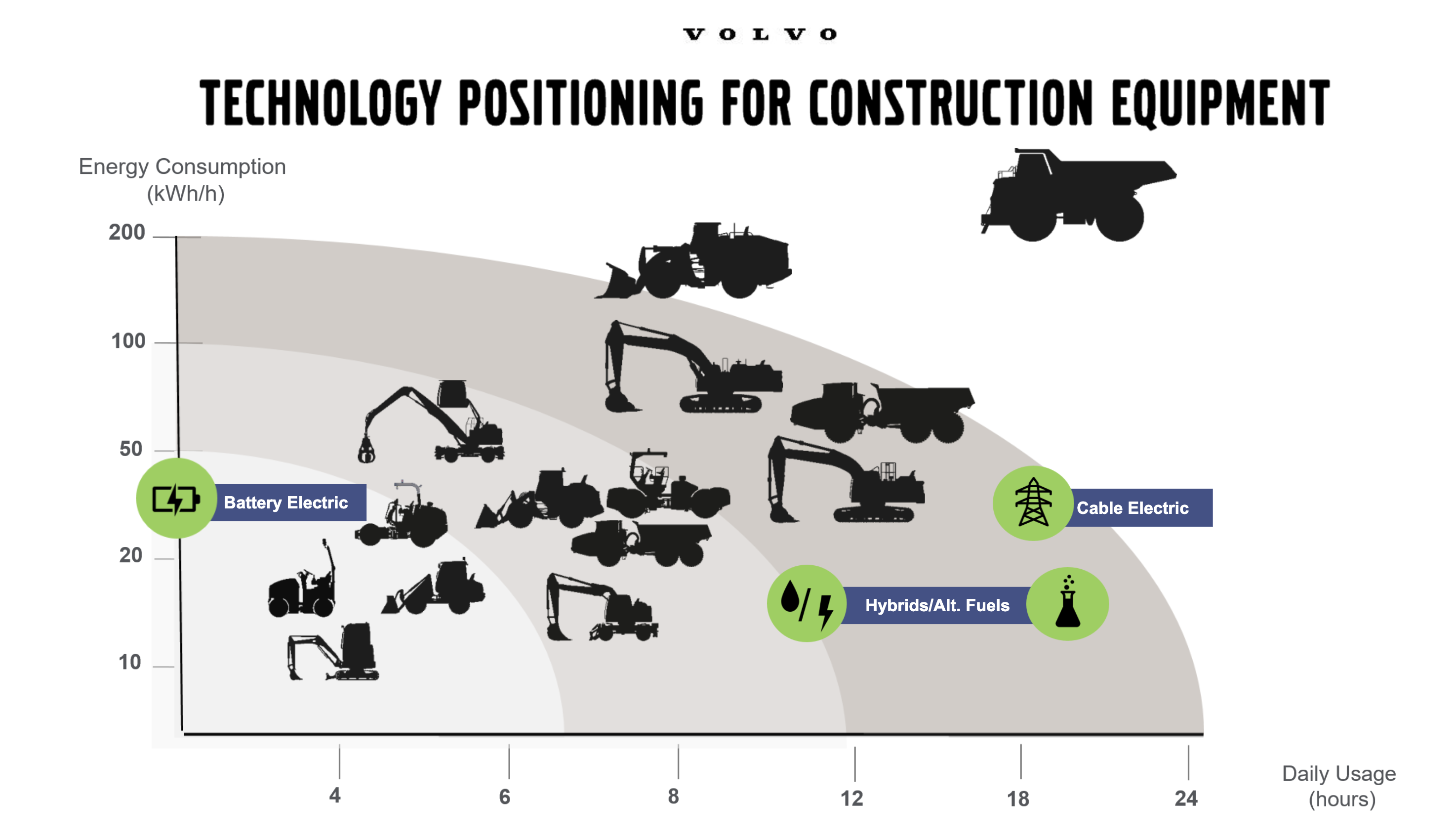

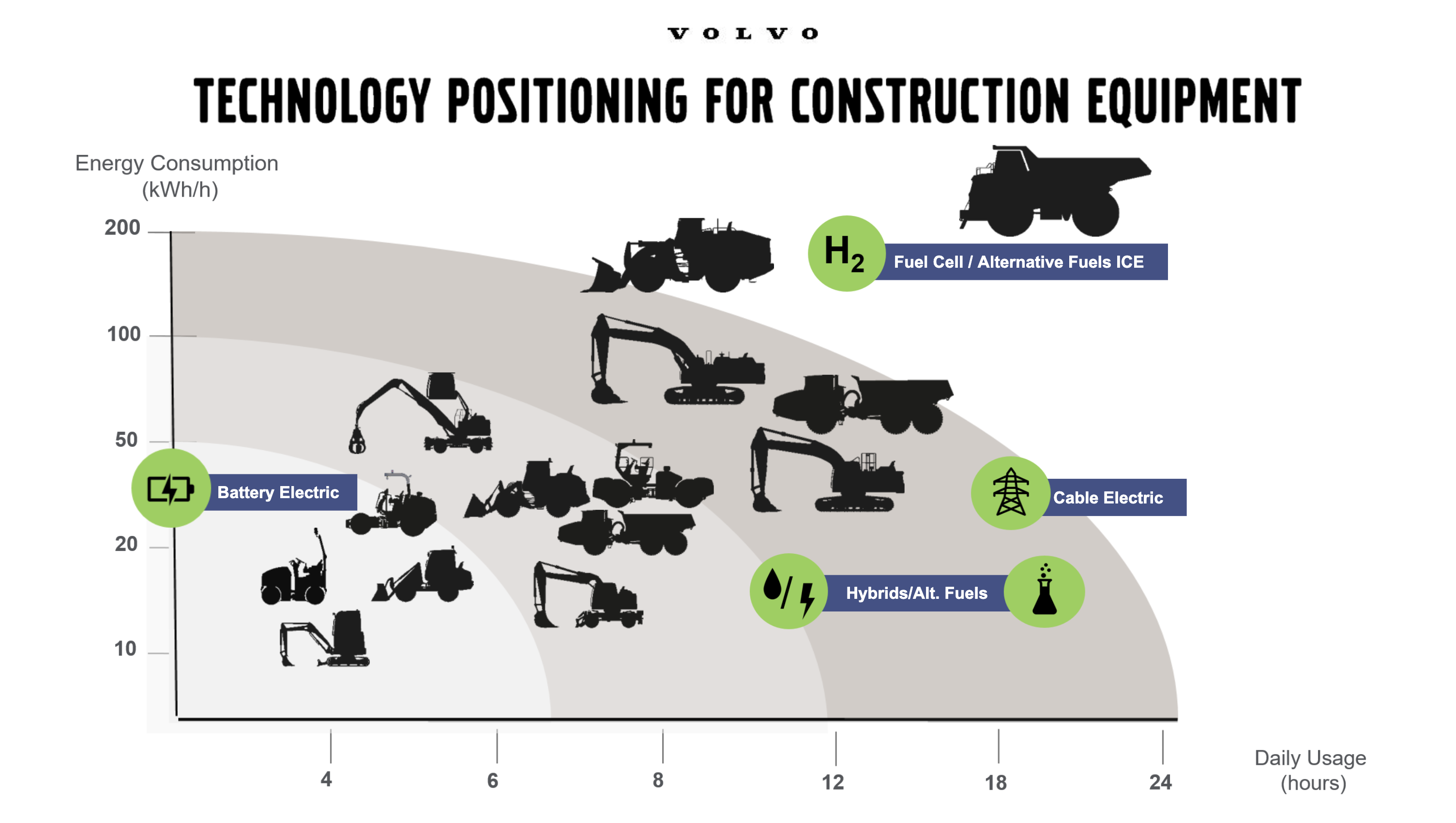

I see the evolution of electrifying heavy construction like this. First, we need to realize that the solution to electrification or sustainable power in heavy equipment isn’t just a single technical solution but a variety of different solutions we’ll need to develop and bring into play.

The chart above displays power on the vertical axis and hours of duty cycle per day on the horizontal axis. If you take the small equipment at the bottom left corner of that graph, you can see that they lend themselves well to a simple battery-electric drive. At Volvo, we put a 48-volt battery pack in our compact machines that can store enough energy so that the machines can do their duty cycle during the day on a typical duty cycle basis. We have different chargers available as well.

Even if you get into the heavier machines above 50 kilowatts – up to about 100-120 kilowatts – we could power those using a battery pack. The only difference is the battery pack goes up to a much higher voltage – 600 volts in our case – so that we can get faster charging times and the power we need out of it with a reasonable weight/power balance.

Beyond that, once we get over about 120-150 kilowatts of power requirement and longer duty cycles, we have to start looking at different technologies. The simple reason is that the batteries are too heavy to supply the kind of power we’re going to need, which is especially true for applications where machines are used continuously for 24 hours – not to mention the charging times are too long on these very large battery packs.

As a result, we’re looking at different technologies like hybrids and alternative fuels that will be able to power these systems going forward – and even cable electric machines where you connect the machine directly to the grid and draw power that way while the machine is working. That’s a good option if you happen to have a stationary machine or application.

When you get into the very large equipment over 200 kilowatts, we’ll have to look at some of the more exotic technologies like hydrogen power, where you can either do a hydrogen powered direct combustion engine, which is a modification of a standard diesel block, or we can supply electric energy from a fuel cell to power the machine. These options are available, and they can take us up into the very high-power ranges like you would see in mining or on quarry sites.

When you get into the very large equipment over 200 kilowatts, we’ll have to look at some of the more exotic technologies like hydrogen power, where you can either do a hydrogen powered direct combustion engine, which is a modification of a standard diesel block, or we can supply electric energy from a fuel cell to power the machine. These options are available, and they can take us up into the very high-power ranges like you would see in mining or on quarry sites.

A final note: One of the considerations for all these power ranges and different technologies is that we’ll need to be much more efficient as OEMs to recapture as much of this energy as possible while the machines are being used. If you have a battery pack with limited power, you can’t afford to be wasting or losing power through an inefficient system. That’s why as manufacturers, we’ll need to be more effective in how we use the power and how we recover it in the non-work cycles to make the machines and battery packs last as long as possible.

Dr. Ray Gallant is a Vice President of Sustainability and Productivity Services at Volvo Construction Equipment.

Discussion

Be the first to leave a comment.

You must be a member of the BuiltWorlds community to join the discussion.