At last week’s BuiltWorlds CEO Forum Meeting, University of Chicago economist and co-author of a recent report on productivity in construction Chad Syverson sparked heated debate when he suggested that the gap between productivity growth in the broader U.S. economy as compared to the lag in construction industry productivity over the past 50 years, now shaves $2.8 trillion per year off of U.S. GDP, annually. That is $2.8 trillion per year less output that people are getting in activities such as housing construction and infrastructure construction that are critical to key national priorities such as addressing housing affordability and repairing our failing infrastructure.

While the industry debates the accuracy of the report and what might be behind the findings, calls are growing in circles outside of the industry for more action to address the problem, leading to speculation that growing frustration with the industry could spark a broad wave of policy action affecting the industry.

Shock, Anger and Skepticism that the Industry Actually Has a Productivity Problem

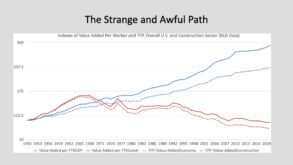

Over the course of his 90-minute presentation, Syverson methodically presented the data behind his and his colleague Austan Goolsbee’s conclusion that construction productivity, which grew from the 1950s until the 1970s in their analysis, took a turn for the worse and began a decline which continued from the 1970s through at least 2020, the end of their data collection.

Industry executives in attendance peppered Syverson with theories for possible flaws that could account for the findings, and as a group theorized what changed in the 1970s that resulted in the flaw, however the research methodically accounted for inflation and a range of other factors such as labor costs, material inputs, IP valuations, capital investment and even complexity of projects.

If The Industry Accepts that It has a Deep Productivity Problem, Why are the Root Causes So Difficult to Diagnose?

Beyond questioning the fundamental accuracy of the report, which was based primarily on data in the housing sector, the question then turned to an attempt to try to understand why. The group spent considerable time discussing increasing complexity in buildings and also in the code requirements around buildings. However, it was observed that cars and other products have become more complex and subject to more regulation than in the early ’70s, while still experiencing gains in productivity. In fact, Syverson admitted, “We have not found a smoking gun” – while the report ruled out many potential factors that may have led to the failing in productivity in the sector, the data did not point to any clear, specific causes.

In the absence of a clear culprit, the group deliberated on what might be at least major contributing factors and touched particularly on three areas of possible cause that seemed suggested in the report’s data:

- Declining skill levels in the industry’s labor pool: This hypothesis was fueled by discussion that construction activity had increased in states where productivity was lower than in states where productivity was higher, leading to speculation that construction demand may be rising faster in areas where workers have lower skills on average than in slower growing, mature markets where higher percentages of workers may have more tenure and training.

- Lack of widespread commercialization of truly new construction equipment since the 1970s: From the 1920s until the 1970s, the construction industry witnessed the introduction of a wide array of important, new equipment, including the bulldozer, the compactor, the payloader, the tower crane, the scissor lift, and the ringer crane. The past 50 years, however, has not seen a similar period of widespread introduction of new products as much as incremental improvements to existing tools and equipment.

- Fragmentation and specialization in the industry and its associated contracts: Almost since the construction management delivery method gained prominence in the United States, over the traditional design/bid/build approach, proponents of so called alternative delivery methods such as design/build, integrated delivery and “industrialized construction” began gaining currency as antidotes for the ills of fragmentation. This document, issued by the Construction Management Association, helps describe how this shift occurred in the 1970s, introducing many more companies into the process of developing, designing and building projects.

Who Will Solve the Problem: Industry Leaders or Global Policy-Makers?

Lest there be a perspective that construction productivity is a uniquely American problem, Syverson also illustrated that construction productivity lags broader economic productivity in 16 of 29 OECD countries. The United States lags behind most countries, but others are equally struggling and, as a result, we are beginning to see policy action in places like Canada and Japan, as well as calls for policy action in the United States. The Canadian prime minister recently toured Canada touting a series of programs to support projects that leverage emerging technology, including robotics, 3D printing and modular housing.

Meantime, in the United States, suggestions for similar actions along with calls for more training support are circulating. How far governments will go in the effort to reform construction “from the outside” and what shape policy takes remains to be seen. Perhaps just as important may be the question of whether industry leaders will move in a more concerted and aggressive direction toward accepting the need for action and taking bolder steps themselves to reverse the industry’s slide.

Discussion

Be the first to leave a comment.

You must be a member of the BuiltWorlds community to join the discussion.