The construction industry is battling a complex headwind of overlapping and intersecting challenges that threaten to restrain the built environment’s growth and development. It’s a situation that has fueled the incubation of innovation while also underscoring the complications of truly incorporating those new technologies that promise the most impact. This is particularly true as it relates to robotics.

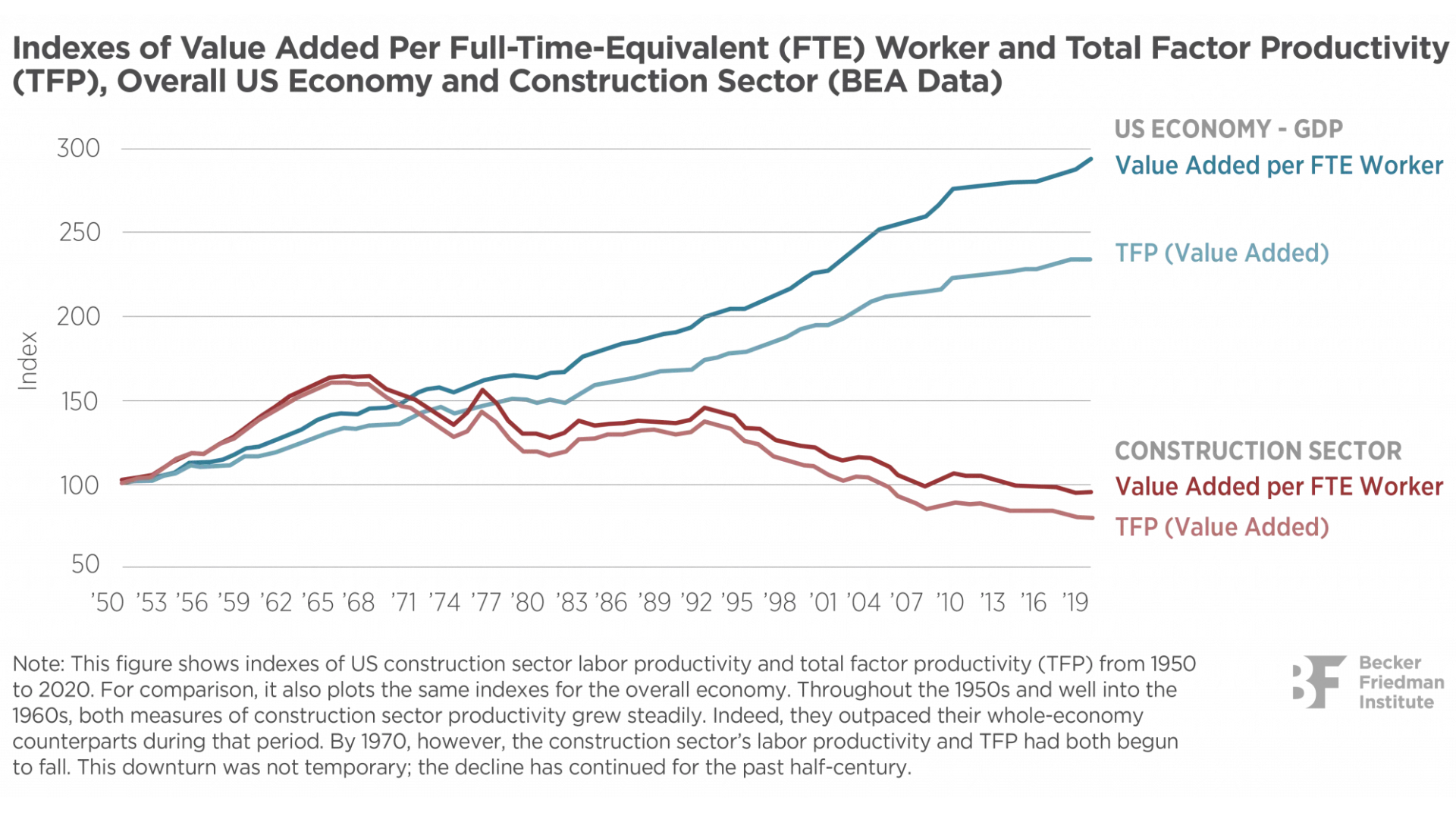

Robotics offers a solution to some of construction’s most pressing problems. Those challenges include a labor gap that exceeded half a million in 2024; an exceptionally high rate of workplace fatalities, of which construction accounts for nearly a fifth in the US; and a half century-decline in productivity—increasingly fueled by the effects of climate change, with adverse weather now delaying nearly 45% of projects worldwide—that reportedly reduces US GDP $2.8 trillion annually.

As a supplement to unavailable labor, a safeguard against the inherent dangers of construction work, and a tool by which contractors can, at least theoretically, boost productivity in a wide variety of circumstances, the promise of robotics is compelling. It begs the question: Why isn’t adoption of the technology more widespread?

The answer is, in no small part, risk.

The Risks of Robotics

As a risk-averse industry, on-boarding any potentially disruptive technology in construction is a rigorous, comprehensive process that aims to understand its impact completely, including its risk. Robotics is unique in that the risk can be difficult to assess—a pill particularly hard to swallow when you consider the considerable upfront cost of robotics, another major deterrent to the technology.

Risk of the Unknown

Craig Maiwald is a robotics business development manager for Hilti North America, the company behind Jaibot, a semi-automated robot designed for mechanical, electrical, plumbing and interior finishing installation work. He explains that part of what makes robotics such a perceived risk is that the technology is so unknown.

It’s not like replacing ladders with scaffolding, Maiwald says, where a company could easily compare rates and types of associated injuries, not to mention talk with employees that likely have experience with both. “There is no data unless you get a robot on your site,” he explains. “They don’t have a risk assessment.”

Risk of Liability

There’s also the liability risk.

“Even in the contractual agreement, the risk is always on the operator,” says Maiwald, who compares it to any other type of tool. “I cannot control anything on a job site. I have no ability to control any of the environmental conditions. So the risk does fall to the user, the operator, those renting, leasing, or buying and using the gear.”

It’s unclear how contractors might weigh that risk against the technology’s potential value. At least in some instances, the decision seems to be driven by a level of prudence that approaches anxiety.

Hardhat Robotics Founder Henning Roedel, who holds a PhD in civil and environmental engineering from Stanford University and previously served as robotics lead for global construction giant DPR Construction, explains a past instance in which a contractor refused to employ a semi-autonomous crane load stabilizing technology, designed by Vita Inclinata, over worry of a “potentially organization-ending type of disaster.”

“Risk and insurance became a big roadblock,” Roedel says, “in the sense that if something were to go wrong on the crane for whatever reason … (the GC) would open themselves up to some sort of liability.”

The catch-22 was that the technology is designed to reduce the risk of the task being performed. By avoiding the risk of liability altogether, he explains, the operators ended up facing what was potentially a more risky scenario.

“Perceived risks like the Vita Inclinata one really irk me,” Roedel admits, “because there’s already a tremendous risk on people using taglines and getting caught up in it.”

Risk of Displacement

Finally, there’s the risk of worker displacement, an understandable fear rooted in statistics.

Take manufacturing, for instance, an industry that’s widely embraced robotics. While evidence shows the introduction of robotics to manufacturing has boosted productivity, it also shows resulting reductions to both the workforce and wages. A report from MIT found that in the US, the introduction of a single robot in manufacturing, on average, resulted in the loss of three jobs nationally.

Of course, manufacturing and construction aren’t directly comparable, with vastly different demands and processes. Still, with limited data available, the impact robotics has had on manufacturing may be misconstrued as foreshadowing.

“I think it’s very natural to assume that you could be displaced by (robotics),” says Jorge Tubella, robotics and research lead for Haskell, a global leader in construction known for its innovation. But as he’s quick to make clear, assuming something doesn’t necessarily make it true. “In 2017, the thought was these (construction) robots were going to be displacing workers. It’s turning out to be the complete opposite right now.”

Mitigating the Risks of Robotics

By and large, contractors are wary of the risks presented by the current generation of construction robotics, and it doesn’t come as much of a surprise—even to proponents of the technology, who’re working to quell those fears. The risks are understandable. The technology is relatively immature, comes at a significant cost, and in most circumstances the operator, whether a contractor or subcontractor, assumes all liability in the event of an injury, incident, or failure to live up to expectations.

Still, for all the unknowns and looming worst-case scenarios, the industry is finding ways to mitigate these risks, dispel fears, and increase the overall appeal of robotics.

Differentiating Robotics and Construction Robotics

Part of the effort to reduce the apprehension to incorporate construction robotics is simply combatting ignorance and confusion around the technology.

Widespread misconceptions about robotic capabilities may be stunting adoption, says Tubella, explaining how external factors, like the influence of sci-fi TV shows and movies, have skewed expectations. “I think there’s a disconnect between end users and what it actually would take to bring a robot onsite and work in a dynamic environment.”

Maiwald explains that disconnect as, in part, the result of drawing false parallels to other industries’ robotics, such as those used in manufacturing and medicine.

“(Construction robotics) need to move, and that changes things dramatically,” he says. “That’s very different from robotics historically, which are almost always fixed to the floor.”

Reconciling the reality of modern construction robotics with the more general and sometimes fantastical ideas of robotics sets the stage for more substantive discussions on the subject.

Being Clear on Capabilities

Confusion around the current capabilities and applications of robotics, in the most broad sense, can also add to fears of job displacement. Tubella warns the industry against this kind of thinking, likening it to artificial intelligence.

“AI is not going to take your job,” he says. “But people that are using AI might.”

In his own circles, Tubella dispels the fear of robotics while encouraging their adoption by framing the technology as a tool to make the overall job easier and the individual’s life better.

“Look how much work (people in the field) have. Look at how much time you’re spending here,” Tubella says. “I’m like, this is here to help you.”

Mihir Somalwar, innovation lead at Diverge, a Hensel Phelps company, and former senior robotics engineer at SafeAI, echoes Tubella’s sentiment, saying that “the robots we use on-site today aren’t taking away jobs—they’re shifting tasks from manual labor to more tech-savvy roles.” He uses the example of layout robots.

“In 2017, the thought was these (construction) robots were going to be displacing workers,” Tubella says. “It’s turning out to be the complete opposite right now.”

“Instead of workers manually laying out lines, a field engineer with a tablet can do the same work faster, more accurately, and more safely,” he explains. “This eliminates exposure to silica chalk dust and reduces physical strain of bending down or walking on their knees all day … This ensures they can have longer, safer, and happier careers.”

Still, how can workers be so sure that robotics truly won’t be replacing them anytime soon? Maiwald puts it simply, saying, “the reality is they’re not very smart.” He says that in all likelihood, if there is a future in which robots replace construction workers on any grand scale, it’ll be a generational shift rather than an immediate one.

“I’m keenly aware that there’s this worry or perception,” Maiwald admits, “but properly these are cobots or collaborative robots that still need an operator.”

Focusing on Safety

At Hardhat Robotics, Roedel and his team use safety as a strategy for buy-in, building robots that only perform STCKY tasks. “It means ‘stuff that can kill you,’” he explains. “I think that’s a perfect opportunity for a robot to go in and perform that task. It’s just a question of ‘do you want that to be automated or teleoperated?’”

It’s an approach that resonates with some contractors, says Tyler Williams, a field innovation leader for DPR, who sees safety benefits as two fold.

“So, the overhead concrete anchor drilling robot—you have the height, which creates a more probable situation for something to happen,” Williams says. “You have silicone exposure. You have repetitive drilling to where now we have strain on our workforce’s shoulders, and over time that’s a pretty expensive incident.”

Williams describes situations in which workers may have to “move dump debris or “flip a breaker for a new data center”—situations where the appeal of a potentially productive robot is compounded by potential safety improvements and long-term cost savings. In considering robotics, he asks the question, “Can we utilize these solutions to either eliminate or create a much safer pathway to finish that work?”

Piloting and Education

Many of the risk concerns, though, particularly about true, in-the-field performance, cannot be dispelled through the mere promise of potential, however tantalizing, as they stem from a fundamental lack of hands-on experience and available data.

“When you’re looking at a new piece of machinery or equipment or a process, you go out and evaluate the risk of a current task,” Maiwald says. “But if you’re going to implement a type of robot to come in and do the new task, you have no ability to assess the risk.”

It’s a chicken or the egg conundrum.

“The challenge,” Maiwald says, “is how do you gain that experience in order to do a risk assessment if you’re unwilling to bring a tool onsite because you deem it to be too risky.”

Some contractors, like Haskell, have invested in internal teams to help test and evaluate outside robotics tech, slowly filling the data void.

“We’ll bring different providers to Haskell to show us their unit and how it works, and from there we’ll try to validate it internally in a sandbox before deploying it onto a site,” says Tubella, who explains that even after a robot is onsite his team continues to manage expectations in the field. “We’re going to let them know: This is the level of maturity within the startup; this is the technology that they’re providing; this is the value you’re going to get back; and these are the parts that might fail.”

Other companies, like DPR, have used pilot programs to test robotic viability.

Williams describes these programs as “smaller-type proofs of concept,” explaining the process as a way to experience the potential benefits while limiting the risks to a project and the people working on it by only applying the technology for smaller scopes of work.

“The challenge,” Maiwald says, “is how do you gain that experience in order to do a risk assessment if you’re unwilling to bring a tool onsite because you deem it to be too risky.”

“First and foremost is worker safety,” Williams says. “Much like we would do if we were doing steel erection on a site, we delineate a work zone. That’s what’s happening here.”

Not only has DPR found the process helpful in terms of collecting data on the technology’s capabilities and performance, but it’s provided lessons into how to best introduce and incorporate the tool, further dispelling fears of worker displacement.

“What we found is education on how the robot would operate, what work it’s performing, and then creating an awareness campaign for all those workers that are on-site … seemed to help quite a bit.”

In at least one instance, Williams explains, the workers even ended up having a naming party for the robot on site. “Let them get familiar with it,” he says.

Data Collection

Of course, not every contractor is in a position to staff internal robotics teams or risk potentially disruptive pilot programs to self-assess whether a robotic technology is truly worth the investment. Maiwald, speaking as a robotics business development manager for Hilti but also as a representative of the robotic manufacturing community, says that manufacturers are generally sensitive to the industry’s overall lack of data and experience as well as the resulting hesitation around the technology.

“I think most of us in the industry are … very cognizant of that,” Maiwald says. “I, like probably any other robot manufacturer, am all too willing to help get a robot on the site to give (contractors) that experience and the data in order to come up with an assessment.”

That willingness, Maiwald explains, is the result of experience with the tech.

“If we believe (robotics are) more productive and safer, and we have quite a bit of experience back that up but the client does not, then just reach out to us,” he says. “We’re confident that it’ll come out in our favor, (and) that you’ll find that operators are not afraid of the gear.”

Discussion

Be the first to leave a comment.

You must be a member of the BuiltWorlds community to join the discussion.