To paraphrase Mark Twain, the rumored death of modular high-rise construction in the U.S. has been greatly exaggerated.

Despite bitter lawsuits that stopped work for eight months, one general contractor’s angry departure, really bad press, and doubts planted by early problems with materials, equipment, project sequencing, and financing, Brooklyn’s much-maligned, 32-story modular high-rise apartment building is rising again.

And looking past all those negatives, owners, developers, and potential investors all are paying attention, keenly aware of what a watershed modular success could mean to the backlogged marketplace. Historically, the case for modular construction invariably touches on speed, safety, quality, waste reduction and savings, particularly when prefabrication is repeatable, as with hospital rooms and apartments.

So, Brooklyn’s ongoing, 346,000-sq-ft experiment, B2 BKLYN, is still well worth studying. In fact, the roughly $200-million project will be the subject of one of the more highly anticipated sessions at BuiltWorlds’ CEO Tech Forum next month in Chicago. There, Roger Krulak, SVP for Modular Construction at Forest City Ratner Cos. (FCRC), will discuss the hard lessons learned from trying something so new in both an industry and a union-dominated town still “set in their ways.”

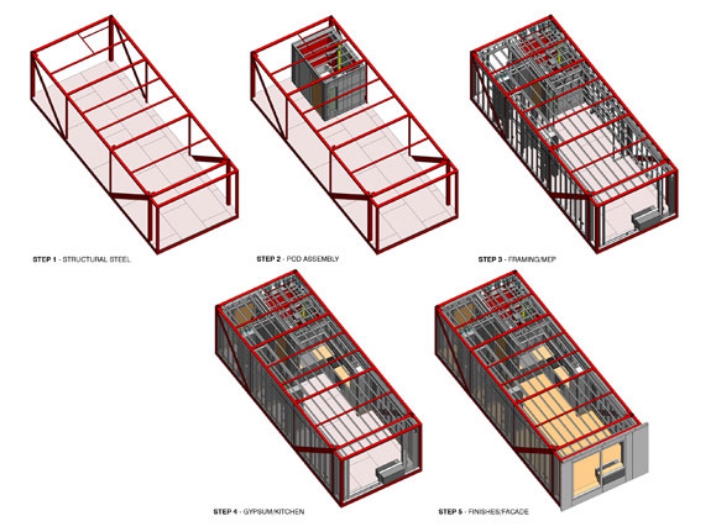

Prior to its much-chronicled setbacks, B2 BKLYN was billed — and may yet emerge — as the modular tower to top all modular towers, one for which intact walls, flooring, kitchens, bathrooms, plumbing, electricity and facades all are delivered on site in a tubular steel-framed chassis, with units measuring up to 10-ft tall, 15-ft wide, and 30-ft long.

The process, says Krulak, is deceptively simple:

1) Assemble components in a 100,000-sq-ft, climate-controlled factory;

2) Transport completed modules 2.5 miles to the project site via flatbed trucks;

3) Lift and stack them on site, as crews erect steel braces, and bolt them into place;

4) Repeat. (One local commentator refers to B2 as the “LEGO high-rise”.)

In all, trades are performing 80% of all construction off site, Krulak says.

\

\

To be sure, B2’s rise to date has been defined by its challenges, the majority involving schedule. But as methodologies are refined, B2 nevertheless represents a potential breakthrough for modular construction, which to date has been relegated to buildings of 10 stories or fewer in the U.S., typically schools and quick-service restaurants. By comparison, B2, designed by NYC’s ShoP Architects, will stand as the world’s tallest modular building upon completion this summer.

As the Modular Building Institute (MBI) tweeted earlier this year, “History is in the making!”

“Modular construction… is faster, less expensive, allows for high levels of quality control and significantly reduces waste and truck traffic. It’s also safer for workers as construction is done inside in controlled environments”

Of course, as we all know, history can be messy, subject to fickle forces like economics, and even the weather. Krulak recalls how the decision to go modular initially stemmed from volatile pricing among local labor. That prompted FCRC to investigate more cost-efficient methods to execute the project, portions of which include affordable housing.

“Rather than pay on-site labor rates of up to $140 per hour, we estimated we could shave 20% to 30% off project costs — a fortune to our way of thinking — if we prefabricated the majority of the facility off site,” he explains. Among other cost savings, the developer also projected that it could shave 10 months off the project’s estimated 30-month construction schedule.

Not surprisingly, local unions initially balked due to potential jurisdictional conflicts, given the overlap that invariably accompanies the multiple sites needed for one modular project. FCRC held its ground, though, negotiating “non-jurisdictional” contracts for the project, according to Krulak.

Labor Pivots

Union workers not only relented, but agreed to work at lower wage rates. The tradeoff? Some 250 tradespeople were guaranteed steady, year-round work, regardless of the weather. “They’re also learning to execute a concept that is gaining greater traction, and for a building type for which many had priced themselves out of business in New York,” says Krulak, citing the logic in the unions’ pivot. “Now they’re back in.”

B2’s towering height resulted from extensive research conducted jointly in 2011 by FCRC, structural engineer ARUP, and a modular consultant. Six months and 600 pages later, their collaboration yielded an approach involving a “bolt-together brace frame” capable of accommodating a 32-story structure. Earlier studies had ruled out concrete framing, not only because of requirements for a large precast plant, but because, relative to steel, “concrete isn’t particularly flexible for purposes of bolting,” Krulak says.

With structural plans in place, FCRC declared it had “cracked the code” to achieving heights previously deemed unfeasible for modular buildings. To fabricate modules, the developer and project contractor Skanska USA Building together established a modular housing joint venture, with fabrication to occur in a Brooklyn Naval Yard facility.

Had all gone as planned, the approach could have established an instant template for cost-efficient construction of large-scale affordable housing.

But all did not go as planned.

Soon after breaking ground in December 2012, fabrication began to fall behind, further and further. As a result, by April 2014, only five of the structure’s 32 stories had been put in place. At the time, FCRC attributed the delays to the fact that it had taken longer than anticipated to set up shop at the fabrication facility, to train laborers, and to establish a reliable supply chain. By August 2014, only five more stories had been added, allegations were flying back and forth, and fingers were being pointed.

Frustrated, Skanska withdrew from the project at that time, amid a rumored $50 million in cost overruns, effectively bringing construction to a halt. Lawsuits ensued, with Skanska alleging faulty design plans and insufficient financial support, and FCRC countering that workers weren’t properly trained, and that the contractor had “blindsided” the developer with its abrupt withdrawal and site shutdown. (For a mammoth archive of all the juicy details, click here.)

The lesson? With true innovation comes great risk, and in this case, a very steep learning curve.

Lessons Learned

“Building a building and starting up a business are two very different enterprises,” Krulak acknowledges. “And startups have their own challenges, too, in this instance greater mastery of material purchases, engineering, installation and tricks of the building trades. Once you’ve accomplished it, though, modular is an incredibly effective means of executing building projects.”

“Not only did Forest City engage in a fairly unique process, but applied it to the world’s tallest modular building,” says MBI President Tom Hardiman. “I do think the project demonstrates that this type of construction can be utilized for taller buildings.”

Lawsuits have yet to be settled, of course, but B2 is now back on track, as part of a larger, $4.5-billion planned development known as Pacific Park. FC Modular, FCRC’s modular housing division, bought out Skanska’s interest in the enterprise and resumed work in April 2015, with NYC-based Turner Construction Co. serving as general contractor on site. Following this summer’s completion, occupancy is slated for fall. Throughout it all, FCRC remain bullish on both B2 and the “modular business model.”

- WATCH > Global stage: Krulak presents last fall at Digital Construction Week in London.

“Given our current capacity, buildings of 15 to 25 stories hit our sweet spot,” Krulak says. “But that doesn’t mean we wouldn’t go larger… or smaller.”

In June, FCRC appointed Susan Hayes, previously with NYC-based contractor 5 Elements West, to lead FC Modular, signaling its commitment to modular construction once B2 is completed. However, in December, FC Modular sounded a grimmer bell, indicating it may lay off as many as 220 employees this spring unless other projects materialize.

“There will be an evolution of FC Modular,” says Krulak. “We’re not sure what it will be, but should have a better idea in the months to come.”

The announcement followed on the heels of news that Brooklyn-based modular manufacturer Capsys planned to shutter its operations after nearly 20 years in business. Neither occurrence necessarily signals a setback for modular construction.

“Hotel chains are contacting us regularly,” says Hardiman, “So are colleges, for which construction can be completed over a summer. And multifamily requests are off the charts.”

“Hotel chains are contacting us regularly. So are colleges, for which construction can be completed over a summer. And multifamily requests are off the charts”

Hardiman remains optimistic about the applicability of the approach to buildings of all sizes. “A 32-story modular structure is still the exception rather than the rule, but we’ve seen a significant increase in four- to five-story buildings utilizing modular construction over the past five years. The UK has several examples of modular buildings in the 10-story to 25-story range.”

Cost savings and time savings continue to drive interest in the concept, Hardiman notes. In a recent study of 17 modular buildings and 17 conventionally constructed structures of comparable size and use, Ryan Smith, associate professor and director of the University of Utah‘s integrated technology & architecture center, found that schedules can be slashed by 45% with modular, and costs by 16% relative to conventional methods.

Still, the small sample size renders the data “difficult to make statistical arguments or identify trends,” the study concludes. So, the jury is still out on modular construction.

But more evidence is mounting every day.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________

Rob McManamy contributed to this story.

Discussion

Be the first to leave a comment.

You must be a member of the BuiltWorlds community to join the discussion.