Long-term gains: Opened in late 2013, Walgreens’ 13,995-sq-ft store in Evanston IL is the national drug store chain’s only NZE facility. Initial costs were 50% to 60% higher, says the owner, which estimates payback will take 15 years.

by JOHN GREGERSON | Dec 17, 2015

Deerfield IL-based Walgreens operates one. So does an elementary school in Bowling Green, KY, a county library in Castro Valley CA, and an apartment complex in Portland OR. Even an entire 18-home eco-village in River Falls WI now is part of the movement.

It may be a stretch to suggest net-zero energy (NZE) buildings – facilities that consume only as much energy as they sustainably harvest – have gone main street. But they certainly are generating greater interest these days, as evidenced by the steady traffic for the Net Zero Pavilion at Greenbuild 2015 in Washington DC last month. Still, various industry estimates indicate that only 400 NZE buildings currently exist worldwide, about a quarter of them in North America. And according to the U.S. Dept. of Energy (USDOE), the majority of those structures are no larger than 15,000 sq ft. But that will change.

NZEs will proliferate in the U.S. in the years ahead, thanks to Executive Order 16393, Planning for Federal Sustainability in the Next Decade, a March 2015 White House directive to the U.S. General Services Administration. It requires “energy net zero by fiscal 2030 in all new construction of federal buildings greater than 5,000 gross sq ft that enter the planning process in fiscal 2020 or later.”

Of course, whether the private sector will follow suit remains to be seen. Despite benefits ranging from much lower building life-cycle costs to eco-enhanced branding, NZE remains a tough sell. Among the reasons are the complexity of NZE facilities and, typically, corresponding hikes in project costs, given the concept informs nearly every aspect of design, from building orientation, massing and geometry to shading, daylighting and site selection. Project team members not only must integrate these variables with curtain wall, roofing, lighting and HVAC systems, but on-site renewable energy, as well, typically solar, or wind, or a combination.

Approaches differ, but LED lighting, shading devices and geothermal heating and cooling frequently figure into the equation, as do radiant flooring, open ventilation, double- or triple-pane glazing, reflective roofing and additional insulation. So, let’s compare the costs and benefits…

ISSUE #1: No Pain, No Gain

“Some owners believe the first costs are simply too high, or they fail to make the connection between higher initial investment and the potential for advantageous payback periods and life-cycle costs,” says Charlie Popeck, president of Phoenix AZ-based energy consultant Green Ideas. Nevertheless, first costs and payback periods can be highly variable, depending on the project, he cautions.

USDOE’s 220,000-sq-ft National Renewable Energy Laboratory in Golden, CO, a facility completed in 2010, achieved NZE with no increase in cost, an achievement that has since proved the exception rather than the rule. For its new 13,995-sq.-ft. store in Evanston, IL, the only NZE facility that Walgreens has constructed to date, first costs were 50% to 60% higher relative to comparable facilities, with an estimated payback of 15 years, says Jamie Meyers, now sustainability leader with architect VOA, Chicago. He was Walgreens’ sustainability manager at the time the project was undertaken.

“ We calculated that the increase in first costs would amount to the cost of two television commercials.”

“We had to make a business case for it,” Meyer recalls. “With Walgreens, you always have to make a business case.” In this instance, Meyer and colleagues persuaded management that a NZE facility would build on Walgreen’s reputation as a leader in sustainable design, particularly in the areas of solar energy and electric charging stations for vehicles. “We calculated the increase in first costs would amount to the cost of two television commercials,” says Meyers, who acknowledges the retailer anticipated the project would also garner plenty of favorable national publicity, which it did.

Speaking at the grand opening in November 2013, Walgreens President of Operations Mark Wagner framed the project as part of a broader mission. “We have facilities that utilize wind turbines, solar installations and geothermal technologies, (but) this is the first time we are bringing all three together in one place,” he said. “Our purpose as a company is to help people get, stay, and live well, and that includes making our planet more livable by conserving resources and reducing pollution.”

So far, Walgreens is still expecting its long-term investment to pay off.

- Above, take a video tour of the new net-zero attraction at the University of Illinois.

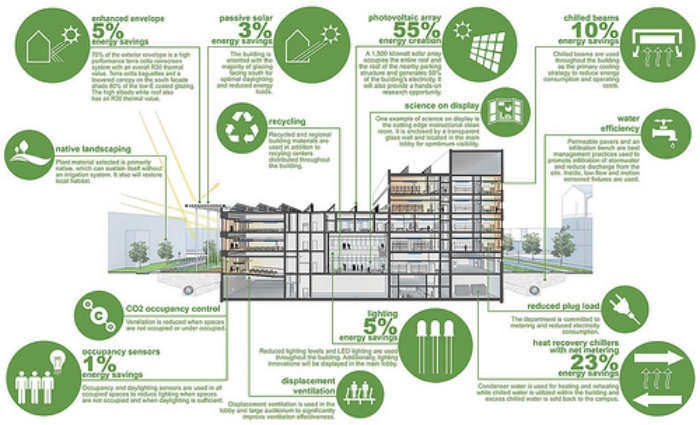

Not surprisingly, as the green movement has continued to grow, many universities now believe that sustainable design can help attract top faculty and students from all over the world. If so, that justifies the premium. Such was the thinking behind the University of Illinois‘ new College of Electrical and Computer Engineering (ECE) Building on its Urbana-Champaign campus. Supported in part by Texas Instruments, Intel, the Caterpillar Foundation, the $95-million, 230,000-sq-ft facility will achieve NZE once installation of a photovoltaic solar array is completed early next year.

Here, first-cost premiums were lower than those of Walgreens, about 5% to 8% higher than for buildings of comparable size and use, according to Phil Krein, a professor of electrical engineering and former chair of the college’s new building committee. Payback will be achieved, he says, in “a little less than eight years, which is pretty quick for a 100-year building.”

Home to more green buildings on a per capita basis than most large U.S. cities, the District of Columbia in 2014 asked its Dept. of the Environment, the New Buildings Institute, International Living Future Institute, and contractor Skanska all to assess the costs and benefits of NZE buildings and other sustainable options. Their finding?

“The initial cost for energy efficiency is approximately 1% to 12% higher, varying by building type,” according to a statement by Skanska. “This rises to 5% to 19% in NZE buildings when considering the added cost of photovoltaic power. But the benefits make the added cost worthwhile: the energy efficiency measures alone offer a return on investment of 6% to 12% [per year].”

Factor in tax breaks and payback time accelerates, sometimes significantly, Skanska concluded.

ISSUE #2: Playing the long game

Of course, some segments still won’t bite. “Hospitality tends to flip facilities after a few years,” says Meyers. “If you’re not in it for the long haul, you’re not going be around for a payback. So there’s no incentive.” For the same reason, “I’ve never heard of a spec building achieving net-zero,” says Ben Heymer, senior project manager with energy consultant Seventhwave, Chicago, which participated in the Walgreens project.

End use also influences the decision, adds Popeck. For that reason, energy guzzlers such as data centers and chip manufacturing plants are not ideal candidates for NZE, he says.

All natural: 849 panels now shoulder the energy load.

Even some renewables pose hurdles. “The regulatory environment for wind turbines remains very unpredictable,” says Heymer. That explains why Walgreens drastically reduced its plans for wind-generated energy at its Evanston project, where a revised site plan added to the legal uncertainties to dim prospects. “The more we investigated wind, the more we realized how difficult it was going to be to identify a partner we were sure would be in business long enough to complete the project, or to supply a product we were certain was reliable,” says Meyers.

Instead, Walgreens relied almost solely on 849 rooftop solar panels to generate 256,000 kWh per year, save for a pair of 35-ft.-tall turbines, mostly for show, that generate 10,000 kWh.

Similarly, the University of Illinois also rejected wind power after performing extensive studies. It opted instead for a solar-only plan. “The technology just didn’t seem ready for prime time,” says Krein.

As with renewables, some geometric forms may prove more advantageous than others.

“Long and and narrow allows you to maximize daylighting, which is going to help you reduce heating and lighting costs,” says Meyers. Tall structures can present problems due to their relatively small roofs, which may limit the size of solar installations. Conversely, one-story and two-story structures may more readily accommodate requisite quantities of solar energy, particularly if rooftops are large relative to the structure’s square footage. Even then, designers may find themselves pinching every square inch to achieve desired energy loads.

For the three-story to five-story ECE building, planners utilized every square inch of the facility’s 42,000-sq-ft roof to install solar panels, as well as the roof of an adjacent parking structure. “We’ll eventually need to install additional arrays to ground parking,” says Krein.

For its part, Walgreens also faced issues with its rooftop installation. Because the site dictated a footprint that deviated somewhat from north south orientation, optimal for harvesting solar energy, early analysis indicated that panels would need to be angled seven degrees to meet project objectives, resulting in a roof slope of 19 to 60 feet. The solution was to segment the roof and rotate it on a north-south axis, offsetting it from the underlying structure to achieve a panel angle of only three degrees.

ISSUE #3: SETTING SharEd Goals

Meyers believes efforts to achieve NZE would have failed had not all Walgreens stakeholders been on the same page from the project’s inception, including the general contractor, energy consultant, candidate suppliers, store employees and maintenance staff, all of whom attended a kick-off meeting for the project and participated in planning from that point forward.

“It’s got to be an integrated effort,” Popeck agrees. “In addition to your general contractor or construction manager, you might also want to have some of your specialty contractors, including mechanical and electrical, on board as early as programming or schematics.”

By comparison, traditional procurement methods, notably design-bid-build, may not be as conducive to achieving NZE. “Sustainable initiatives can veer off track as the project is handed off from owner to architect and architect to contractor, ” says Heymer. “They either slip between the cracks or become subject to mistranslation.”

State law prevented UI from circumventing design-bid-build for the ECE contract. But, “the low bidder may not necessarily be the most knowledgeable about sustainable design,” notes Krein. “In our case, we were fortunate to have an architect and HVAC engineer highly experienced in sustainable design to bring our contractor up to speed, though it took some time. It was an intense process.”

For best results, some consultants, Popeck included, advocate a four-step process that begins with optimizing building orientation, followed by design of an energy-efficient envelope, specification of key mechanical components and, finally, selection of renewables. “Unless you first execute steps one through three, you may find yourself wasting money on solar, wind, and so forth, ” says Popeck.

Opinions on the approach are split. “We performed all those tasks in tandem, but I always advise project teams, ‘Don’t do what we did,’” Meyers says.

“Our primary goal was to create a home for our department, with the functionality of our building program being our number-one priority,” says Krein. “It was only when those program elements were in place that we let our architect loose on the exterior.”

ISSUE #4: ENERGY MODELING

Experts are less split on when to introduce energy modeling into the process: Schematic design.

For the Walgreens project, Seventhwave initiated the process with eQUEST, a program developed by the USDOE, “to generate simple box models to determine whether we were on target and could actually achieve net-zero with the proposed footprint,” says Heymer.

As work progressed, Seventhwave transitioned to TRNSYS, a creation of the University of Wisconsin-Madison that allowed project team members to evaluate various interplay among components. The shared goal was to slash energy consumption by 60% relative to a conventional Walgreens. The retailer eventually homed in on a scheme involving shading, natural ventilation, geothermal heating & cooling, and optimization of its frozen foods refrigeration units. It also calculated “plug-in”, meaning the amount of energy store employees were expected to generate once the facility was occupied.

Team members for UI’s ECE building performed similar exercises with e-QUEST and Trane’s Trace 700 to evaluate the interplay among geometries, building orientation, curtain wall and daylighting, in addition to displacement ventilation and chilled-beam cooling.

ISSUE #5: IT ain’t over ‘TIL…

The proof is in the finished facility, which is why commissioning is a must, experts say. So is ongoing monitoring of the facility once it is occupied. “There’s a common misperception the building will perform as planned from day one, which isn’t necessarily the case,” says Heyner, “Sensors, controls automated alerts and alarms are all available to identify and address problems. There’s no reason not to use them.”

For example, the Walgreens store in Evanston did achieve net-zero from March to October this year. The owner still hopes to achieve year-round net zero by the end of this year, notes Meyers. But even if that proves impossible within this timeframe, the benefits long-term will still outpace the costs.

“One of the things we learned was that you can’t necessarily expect to achieve net-zero in the first year of operations,” he adds. “That’s when you discover how all the components are performing. The second year is when you fix problems you discover, and the third is when you hopefully achieve net-zero.”

Of course, for now, 2030 remains the ultimate goal, as the combined forces of both law and the open market continue to drive our industry toward a greener future.

Note: This article is from the BuiltWorlds archives. Some text, images, and links may not appear or function as originally formatted.

Discussion

Be the first to leave a comment.

You must be a member of the BuiltWorlds community to join the discussion.