Cost estimation has come a long way since the days of taking painstaking measurements of building plans by hand and making tabulations with pencil and paper. However, it’s still rarely a simple process, largely because building plans change—sometimes by a lot, often more than once.

Only recently have digital estimation tools started to become sophisticated enough to begin catching up with the ongoing building information modeling (BIM) advancements that have revolutionized and sped up the building design process, reducing the time needed for thorough, accurate estimations from months and weeks to days and hours. But, in order to take things to the next level, more-creative solutions will be needed to better connect modeling software with estimation software, and innovations in VR and—further down the road—generative design could disrupt the estimation process even more.

Model-based estimation

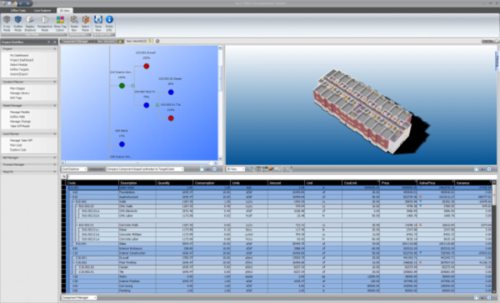

One of the biggest trends in preconstruction is the rising incorporation of BIM in estimation. Using programs such as Autodesk‘s Revit (to create 3-D models from conceptual sets of drawings) in tandem with takeoff software such as Tekla Structures or Vico Takeoff Manager, contractors can extract quantities directly from models and plug them into estimating software such as WinEst, Sage 300 Construction, and Vico Cost Planner to develop early cost estimates for buildings much faster. Not only does this help automate the estimating process; it also allows contractors to more easily accommodate design changes.

“Rather than everybody on the team starting from scratch and redoing quantity takeoffs with each design rendition to determine the magnitude of the changes, the model streamlines the process.” says Neely Sadowski, preconstruction project executive at Pepper Construction, adding that her firm has been using model-based estimating for the past six months to a year. “Design changes can simply be incorporated into the existing model, which will provide revised quantities instantaneously.”

Other firms are trying to make the process even more efficient. Skanska USA, for instance, is now doing “parametric estimating,” in which it links its models to a customized template that allows not only for real-time quantity extraction but also real-time cost-estimation. “You can create a live estimate; you can make design changes or building changes, and as the model updates, you can see how that’s going to update costs, too,” says Kelsey Stein, a Skanska USA estimator and BIM specialist, adding, “You still need to go back and review that information, but it really speeds up the process.”

Others are working on ways to tie models more directly to estimating software, too, but there are so many different estimating solutions that it could take a while. Vico software allows for integration between 3-D models and various estimating programs such as WinEst (which Pepper uses), Timberline, and MC2. However, the database management required to get the models and programs talking to each other is tedious and time consuming. “[That] has slowed our progress in fully utilizing this feature,” Sadowski says, and she’s not sure how far away a solution is. “I think that it is coming, it will just take some time to get all the pieces of the puzzle working together.”

Virtual reality

A report released by Goldman Sachs last year, “Profiles in Innovation: Virtual & Augmented Reality,” predicted that the AR/VR market in the US could be as large as $182 billion by 2025, and a number of construction companies are already seeing ways the technology might be useful in the preconstruction stage.

“It can really help people experience the facility before it’s built and make better decisions,” says Michael Peterson, design phase executive for Mortenson Construction. “And, in some cases, we can even … interact with the environment in real time.” His company specifically combines SketchUp, a BIM solution, with the gaming engine Unity to create models that offer more room for direct engagement. “In other words, imagine you’re working with your end users and design partners and reviewing a headwall in a patient room, and [you] are able to better understand where the outlets should go to improve both the patient and caregiver experience,” he says.

Skanska USA uses VR not only to show what its buildings could look like but to perform what it calls “immersive estimating.” “We can show the client what their building looks like,” Stein says. “We’re moving things, we’re changing materials, we’re changing different design options, and then we’re showing the cost that’s associated with those changes.”

Stein collaborated directly with an Autodesk programmer to develop Skanska’s immersive estimating tool, which incorporates the Stingray gaming engine that Autodesk acquired a couple of years ago. “To my knowledge, we are the only construction company that is using virtual reality or gaming engines with estimating,” she says. “You can plug in a Revit model, and in 30 seconds you can be up and running in VR and do a walkthrough.”

“[In virtual reality], we’re moving things, we’re changing materials, we’re changing different design options, and then we’re showing the cost that’s associated with those changes.”

Computational and generative design

Perhaps even more cutting-edge is the idea of generative design, which Mortenson and others have already begun experimenting with through software such as Dynamo and Grasshopper. The programs use computer algorithms to automatically generate design criteria for a project, producing potentially hundreds of different structural ideas that a human designer might not have the time or energy to think of alone.

“If it’s just one or two people coming up with different concepts, you may be limited to a handful, maybe up to ten,” Peterson says. “If you could explode that and look at hundreds, you can drive a much more efficient design process and optimize cost, quality, schedule, and customer satisfaction—really pulling it all together.”

Like Revit, the generative design software hasn’t been combined directly with any estimating tools yet, but it very well could be soon, and Peterson thinks it might have to be for cost estimation to keep pace with the rest of the preconstruction process. “[Let’s say you have] a hundred design solutions in a week or two,” he says. “How do you provide feedback from a pricing and scheduling perspective for all those in as quick a manner? Right now, a lot of it is manual.”

Basically, whoever ends up cracking the problems of automated cost estimation, it’s safe to say they’ll have an interested customer base.

Discussion

Be the first to leave a comment.

You must be a member of the BuiltWorlds community to join the discussion.