Danielle Dy Buncio, CEO and Founder of VIATechnik, is a regular BuiltWorlds contributor.

We invite experts and thought leaders to share their knowledge on topics related to innovation in the built environment. Information on each contributor can be found at the bottom of each article. Learn more about our contributor program here.

We invite experts and thought leaders to share their knowledge on topics related to innovation in the built environment. Information on each contributor can be found at the bottom of each article. Learn more about our contributor program here.

Unlike other industries, construction has been slow to adopt efficiency-boosting technologies, resulting in stagnant — or declining — productivity.

The future of the construction industry is looking rather rosy these days. As developing nations continue to industrialize and the world’s leading economies rebound from the economic instability of the late 2000s, experts are forecasting a period of rapid growth over the next 15 years.

According to a recent report published by Pricewaterhouse Coopers, “the volume of construction output will grow by 85% to $15.5 trillion worldwide by 2030, with three countries, China, US and India, leading the way and accounting for 57% of all global growth.”

For members of the AEC industry, this kind of news might seem like cause for celebration; in fact, it could actually be cause for concern.

Keeping pace with increasing demand

As buildings and construction projects become increasingly complex, the industry at large has failed to keep pace with technological innovation. According to a recent McKinsey Global Institute digitization index, construction is “among the least digitized sectors in the world.”

The industry, it seems, has been unwilling to commit to new technologies that require up-front investment, despite the apparent long-term benefits they would bring. For example, construction spends less than 1% of revenues on R&D, compared to between 3.5% and 4.5% in the auto and aerospace industries. Information technology investment is also less than 1% of revenues, despite the wide variety of impactful software solutions that have been developed in recent years.

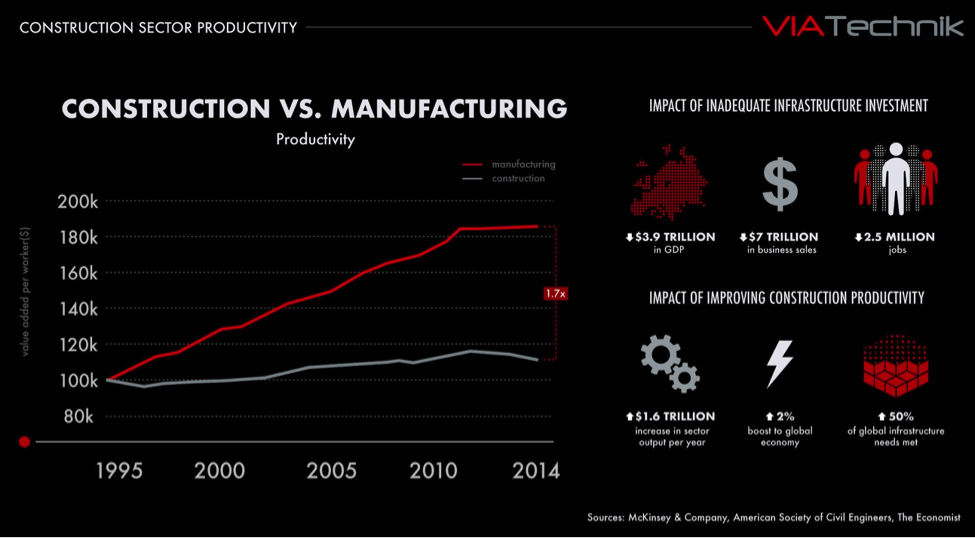

On a macro level, this has had a tangible impact on AEC labor productivity. Over the past decade, the industry only managed an average growth rate of about 1%, year-over-year. By comparison, manufacturing achieved 3.6% annual growth rate, thanks in large part to its adoption of “lean principles and extensive automation.”

The concern is this: as the global demand for infrastructure and housing increases exponentially in the years to come, will the industry actually be able to meet it?

The real-world impact

The American Society of Civil Engineers’ (ASCE) quadrennial Infrastructure Report Card is a perfect example of this problem’s tangible impact. Based on “a comprehensive assessment of the nation’s 16 major infrastructure categories,” the 2017 iteration gave the United States a “D+,” lamenting that “deteriorating infrastructure is impeding our ability to compete in the thriving global economy.”

According to ASCE’s 2016 economic study, by 2025, inadequate investment in national infrastructure will cost us $3.9 trillion in GDP, $7 trillion in lost business sales, and 2.5 million lost jobs. To make matters worse, the estimated cost of improving America’s infrastructure has steadily increased from $1.3 trillion in 2001 to $4.59 trillion in 2017.

In addition to committed investment and strong leadership and planning, the ASCE believes that innovation should play a leading part in making construction efficient enough to affordably and effectively reinforce our national infrastructure. Its report urges stakeholders to “support research and development into innovative new materials, technologies, and processes to modernize and extend the life of infrastructure, expedite repairs or replacement, and promote cost savings.”

Opportunities are emerging

If construction’s productivity catches up to the rest of the pack, it would boost the industry’s output by approximately $1.6 trillion per year. That’s a 2% bump to the global economy, equivalent to 50% of the planet’s infrastructure needs. About 33% of that opportunity is in the U.S. alone.

This wouldn’t be an impossible feat to accomplish — McKinsey explains that by taking proactive measures in several key areas, including “rethinking design and engineering processes”; “improving onsite execution”; and “infusing digital technology, new materials, and advanced automation,” the industry could boost productivity by as much as 60%.

For example, a recent article in the Economist points out that many countries, including the U.K., France, and Singapore, are now requiring building information modeling (BIM) in all public-sector contracts. The hope is that these firms will recognize BIM’s ability to improve project collaboration, cost estimation, scheduling accuracy, and on-site project management, begin using it in more private-sector projects, and give a boost to their economic productivity as a result.

In order to keep up with global GDP growth, the world will have to spend approximately $57 trillion on infrastructure by 2030. As McKinsey points out, this should be a huge incentivize for AEC firms to invest in productivity-boosting technologies and processes. But this isn’t just about increasing the industry’s profit margin. Infrastructure is the backbone of the global economy; it facilitates commerce, transportation, communication — essentially every aspect of our day-to-day lives. In other words, if we fail to evolve our practices and meet the demand for global infrastructure, there’s a whole lot more on the line than just a missed revenue opportunity.

Discussion

Be the first to leave a comment.

You must be a member of the BuiltWorlds community to join the discussion.